TrapC: A C Extension For the Memory Safety Boogeyman

In the world of programming languages it often feels like being stuck in a Groundhog Day-esque loop through purgatory, as effectively the same problems are being solved over and over, …read more

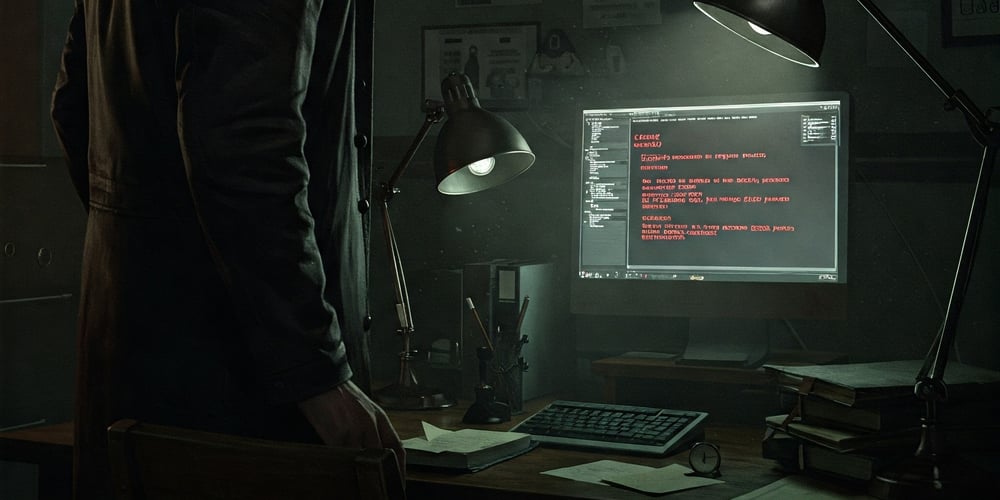

In the world of programming languages it often feels like being stuck in a Groundhog Day-esque loop through purgatory, as effectively the same problems are being solved over and over, with previous solutions forgotten and there’s always that one jubilant inventor stumbling out of a darkened basement with the One True Solution to everything that plagues this world beset by the Unspeakable Horror that is the C programming language.

to everything that plagues this world beset by the Unspeakable Horror that is the C programming language.

As the latest entry to pledge its fealty at the altar of the Church of the Holy Memory Safety, TrapC promises to fix C, while also lambasting Rust for allowing that terrible unsafe keyword. Of course, since this is yet another loop through purgatory, the entire idea that the problem is C and some perceived issue with this nebulous ‘memory safety’ is still a red herring, as pointed out previously.

In other words, it’s time for a fun trip back to the 1970s when many of the same arguments were being rehashed already, before the early 1980s saw the Steelman language requirements condensed by renowned experts into the Ada programming language. As it turns out, memory safety is a miniscule part of a well-written program.

It’s A Trap

Pretty much the entire raison d’être for new programming languages like TrapC, Rust, Zig, and kin is this fixation on ‘memory safety’, with the idea being that the problem with C is that it doesn’t check memory boundaries and allows usage of memory addresses in ways that can lead to Bad Things. Which is not to say that such events aren’t bad, but because they are so obvious, they are also very easy to detect both using static and dynamic analysis tools.

As a ‘proposed C-language extension’, TrapC would add:

- memory-safe pointers.

- constructors & destructors.

- the

trapandaliaskeywords. - Run-Time Type Information.

It would also remove:

- the

gotoandunionkeywords.

The author, Robin Rowe, freely admits to this extension being ‘C++ like’, which takes us right back to 1979 when a then young Danish computer scientist (Bjarne Stroustrup) created a C-language extension cheekily called ‘C++’ to denote it as enhanced C. C++ adds many Simula features, a language which is considered the first Object-Oriented (OO) programming language and is an indirect descendant of ALGOL. These OO features include constructors and destructors. Together with (optional) smart pointers and the bounds-checked strings and containers from the Standard Template Library (STL) C++ is thus memory safe.

So what is the point of removing keywords like goto and union? The former is pretty much the most controversial keyword in the history of programming languages, even though it derives essentially directly from jumps in assembly language. In the Ada programming language you also have the goto keyword, with it often used to provide more flexibility where restrictive language choices would lead to e.g. convoluted loop constructs to the point where some C-isms do not exist in Ada, like the continue keyword.

The union keyword is similarly removed in TrapC, with the justification that both keywords are ‘unsafe’ and ‘widely deprecated’. Which makes one wonder how much real-life C & C++ code has been analyzed to come to this conclusion. In particular in the field of embedded- and driver programming with low-level memory (and register) access the use of union is widely used for the flexibility it offers.

Of course, if you’re doing low-level memory access you’re also free to use whatever pointer offset and type casting you require, together with very unsafe, but efficient, memcpy() and similar operations. There is a reason why C++ doesn’t forbid low-level access without guardrails, as sometimes it’s necessary and you’re expected to know what you’re doing. This freedom in choosing between strict memory safety and the untamed wilds of C is a deliberate design choice in C++. In embedded programming you tend to compile C++ with both RTTI & exceptions disabled as well due to the overhead from them.

Don’t Call It C++

Effectively, TrapC adds RTTI, exceptions (or ‘traps’), OO classes, safe pointers, and similar C++ features to C, which raises the question of why it’s any different, especially since the whitepaper describes TrapC and C++ code usually looking the same as a feature. Here the language seems to regard itself as being a ‘better C++’, mostly in terms of exception handling and templates, using ‘traps’ and ‘castplates’. Curiously there’s not much focus on “resource allocation is initialization” (RAII) that is such a cornerstone of C++.

Meanwhile castplates are advertised as a way to make C containers ‘typesafe’, but unlike C++ templates they are created implicitly using RTTI and one might argue somewhat opaque (C++ template-like) syntax. There are few people who would argue that C++ template code is easy to read. Of note here is that in embedded programming you tend to compile C++ with both RTTI & exceptions disabled due to the overhead from them. The extensive reliance on RTTI in TrapC would seem to preclude such an option.

Circling back on the other added keyword, alias, this is TrapC’s way to providing function overloading, and it works like a C preprocessor #define:

void puts(void* x) alias printf("{}n",x);

Then there is the new trap keyword that’s apparently important enough to be captured in the extension’s name. These are offered as an alternative to C++ exceptions, but the description is rather confusing, other than that it’s supposedly less complicated and does not support cascading exceptions up the stack. Here I do not personally see much value either way, as like so many C++ developers I loathe C++ exceptions with the fire of a thousand Suns and do my utmost to avoid them.

My favorite approach here is found in Ada, which not only cleanly separates functions and procedures, but also requires, during compile time, that any return value from a function is handled, and implements exceptions in a way that is both light-weight and very informative, as I found for example while extensively using the Ada array type in the context of a lock-free ring buffer. During testing there were zero crashes, just the program bailing out with an exception due to a faulty offset into the array and listing the exact location and cause, as in Ada everything is bound-checked by default.

Memory Safety

Much of the safety in TrapC would come from managed pointers, with its author describing TrapC’s memory management as ‘automatic’ in a recent presentation at an ISO C meeting. Pointers are lifetime-managed, but as the whitepaper states, the exact method used is ‘implementation defined’, instead of reference counting as in the C++ specification.

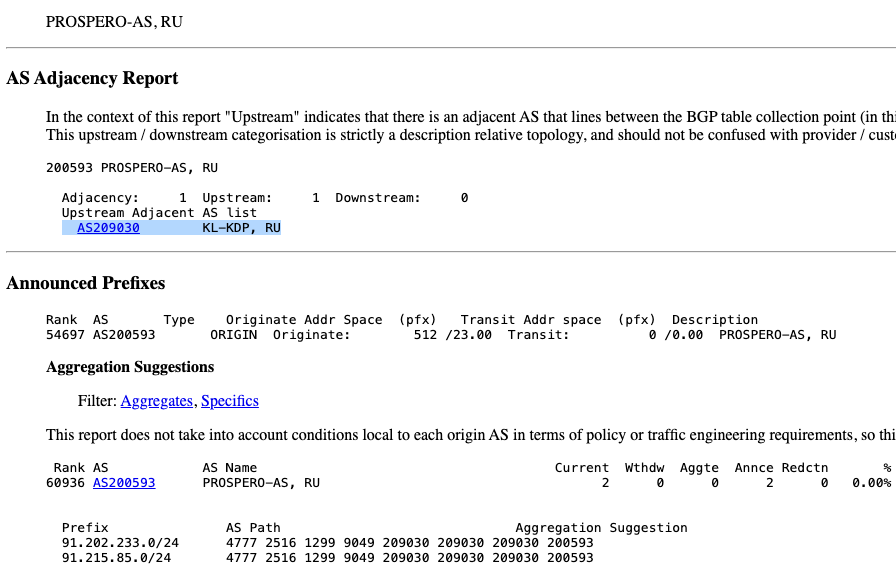

Yet none of this matters in the context of actual security issues. As I noted in 2024, the ‘red herring’ part refers to the real-life security issues that are captured in CVEs and their exploitation. Virtually all of the worst CVEs involve a lack of input validation, which allows users to access data in ‘restricted’ folders and gain access to databases and other resources. None of which involve memory safety in any way or form, and thus the onus lies on preventing logic errors, solid input validation and preventing lazy or inattentive programmers from introducing the next world-famous CVE.

As a long-time C & C++ programmer, I have come to ‘love’ the warts in these languages as well as the lack of guardrails for the freedom they provide. Meanwhile I have learned to write test cases and harnesses to strap my code into for QA sessions, because the best way to validate code is by stressing it. Along the way I have found myself incredibly fond of Ada, as its focus on preventing ambiguity and logic errors is self-evident and regularly keeps me from making inattentive mistakes. Mistakes that in C++ would show up in the next test and/or Valgrind cycle followed by a facepalm moment and recompile, yet somehow programming in Ada doesn’t feel more restrictive than writing in C++.

Thus I’ll keep postulating that the issues with C were already solved in 1983 with the introduction of Ada, and accepting this fact is the only way out of this endless Groundhog Day purgatory.

_Tanapong_Sungkaew_Alamy.jpg?#)

![Sonos Abandons Streaming Device That Aimed to Rival Apple TV [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96703/96703/96703-640.jpg)

![HomePod With Display Delayed to Sync With iOS 19 Redesign [Kuo]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96702/96702/96702-640.jpg)

![iPhone 17 Air to Measure 9.5mm Thick Including Camera Bar [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96699/96699/96699-640.jpg)

_JIRAROJ_PRADITCHAROENKUL_Alamy.jpg?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 139]: The Government Knows AGI Is Coming, Superintelligence Strategy, OpenAI’s $20,000 Per Month Agents & Top 100 Gen AI Apps](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20139%20cover-2.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 138]: Introducing GPT-4.5, Claude 3.7 Sonnet, Alexa+, Deep Research Now in ChatGPT Plus & How AI Is Disrupting Writing](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20138%20cover.png)

.jpg?#)