Here’s what food and drug regulation might look like under the Trump administration

Earlier this week, two new leaders of the US Food and Drug Administration published a list of priorities for the agency. Both Marty Makary and Vinay Prasad are controversial figures in the science community. They were generally highly respected academics until the covid pandemic, when their contrarian opinions on masking, vaccines, and lockdowns turned many…

Earlier this week, two new leaders of the US Food and Drug Administration published a list of priorities for the agency. Both Marty Makary and Vinay Prasad are controversial figures in the science community. They were generally highly respected academics until the covid pandemic, when their contrarian opinions on masking, vaccines, and lockdowns turned many of their colleagues off them.

Given all this, along with recent mass firings of FDA employees, lots of people were pretty anxious to see what this list might include—and what we might expect the future of food and drug regulation in the US to look like. So let’s dive into the pair’s plans for new investigations, speedy approvals, and the “unleashing” of AI.

First, a bit of background. Makary, the current FDA commissioner, is a surgeon and was a professor of health policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. He initially voiced support for stay-at-home orders during the pandemic but later changed his mind. In February 2021, he incorrectly predicted that the US would “have herd immunity by April.” He has also been very critical of the FDA, writing in 2021 that its then leadership acted like “a crusty librarian” and that drug approvals were “erratic.”

Prasad, an oncologist, hematologist, and health researcher, was named director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research last month. He has long been a proponent of rigorous evidence-based medicine. When I interviewed him back in 2019, he told me that cancer drugs are often approved on the basis of weak evidence, and that they can end up being ineffective or even harmful. He has written a book arguing that drug regulators need to raise the bar of evidence for drug approvals. He was widely respected by his peers.

Things changed during the pandemic. Prasad made a series of contrarian comments; he claimed that the covid virus “was likely a lab leak” despite the fact that the vast majority of scientists believe that the virus jumped to humans from animals in a market. He railed against Anthony Fauci, and advised readers of his blog to “break all home Covid tests.” In 2023, he authored a post titled “Do not report Covid cases to schools & do not test yourself if you feel ill.” He has even drawn parallels between the US covid response and fascism in Nazi Germany. Suffice to say he’s lost the support of many of his fellow academics.

Makary and Prasad published their “priorities for a new FDA” in the Journal of the American Medical Association on Tuesday. (Funnily enough, JAMA is one of the journals that their boss, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., described as “corrupt” just a couple of weeks ago—one that he said he’d ban government scientists from publishing in. Lol.)

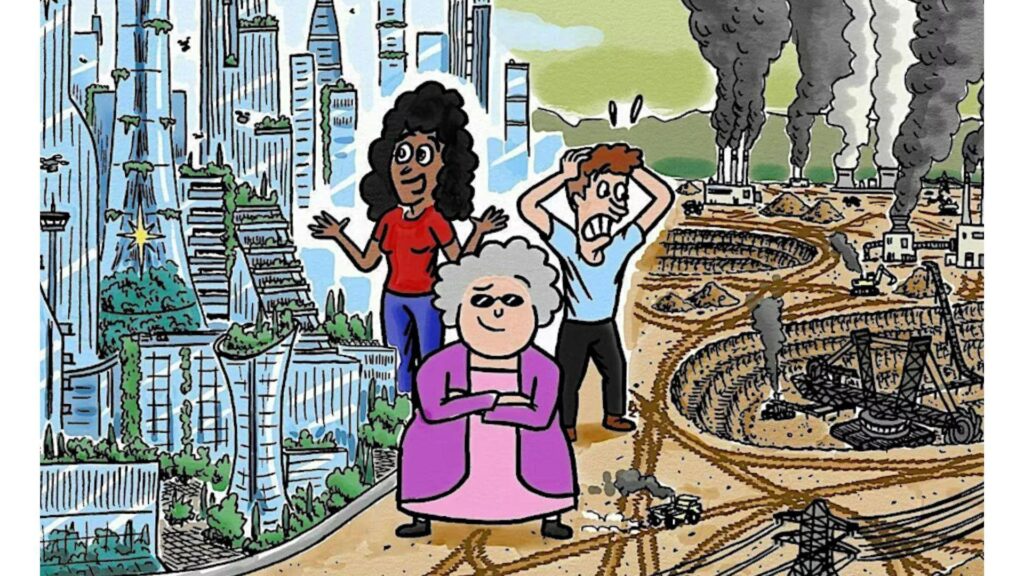

Let’s go through a few of the points the pair make in their piece. They open by declaring that the US medical system has been “a 50 year failure.” It’s true that the US spends a lot more on health care than other wealthy countries do, and yet has a lower life expectancy. And around 25 million Americans don’t have health insurance.

“In some ways, it is absolutely a failure,” says Christopher Robertson, a professor of health law at Boston University. “On the other hand, it’s the envy of the world [because] it’s very good at delivering high-end care.” Either way, the reasons for failures in health care are not really the scope of the FDA, which has a focus on ensuring the safety and efficacy of food and medicines.

Makary and Prasad then state that they want the FDA to “examine the role of ultraprocessed foods” as well as additives and environmental toxins, suggesting that all these may be involved in chronic diseases. This is a favorite talking point of RFK Jr., who has made similar promises about investigating a possible connection.

But this would also go beyond the current established purview of the FDA, says Robertson. There isn’t a clear, agreed-upon definition of “ultraprocessed food,” for a start, so it’s hard to predict what exactly would be included in any investigation. And as things stand, “the FDA’s role is primarily binary: They either allow or reject products,” adds Robertson. The agency doesn’t really give dietary advice.

Perhaps that could change. At his confirmation hearing, Makary told senators he planned to evaluate school lunches, seed oils, and food dyes. “Maybe three years from now the FDA will change and have much more of a food focus,” says Robertson.

The pair also write that they want to speed up the process of approving new drugs, which can currently take more than 10 years. Their suggestions include allowing drug developers to submit final paperwork early, while testing is still underway, and getting rid of “recipes” that strictly limit what manufacturers can put in infant formula.

Here’s where things get a little more controversial. Most new drugs fail. They might look very promising in cells in a dish, or even in animals. They might look safe enough in a small phase I study in humans. But after that, large-scale human studies reveal plenty of drugs to be either ineffective, unsafe, or both.

Speeding up the drug approval process might mean some of these failures aren’t noticed until a drug is already being sold and prescribed. Even preparing paperwork ahead of time might result in a huge waste of time and money for both drug developers and the FDA if that drug later fails its final round of testing, says Robertson.

And as for infant formula recipes, they are in place for a reason: because we know they’re safe. Loosening that requirement might allow for more innovation. It could lead to the development of better recipes. But, as Robertson points out, innovation is a double-edged sword. “Some innovation saves lives; some innovation kills people,” he says.

Along the same lines, the pair also advocate for reducing the number of clinical trials required for the FDA to approve a drug. Instead of two “pivotal” clinical trials, drugmakers might only need to complete one, they suggest.

This is also controversial. A drug might look promising in one clinical trial and fail in another. That was the case for aducanamab (Aduhelm), the Alzheimer’s drug that was approved by the FDA in 2021 despite the concerns of several senior officials. (Biogen, the company that developed the drug, abandoned it in 2024, and it was later withdrawn from the market.)

At any rate, the FDA has already implemented several pathways for “expedited approval.” The Accelerated Approval Program fast-tracks the process for drugs that treat serious conditions or fulfill an unmet need. (Side note: This approval pathway relies on the very kind of weak evidence that Prasad has campaigned against.)

The Fast Track Program serves a similar purpose. As does the Breakthrough Therapy designation. Some health researchers are worried that programs like these, along with other factors, are responsible for a gradual lowering of the bar of evidence for new drugs in the US. Calling for an acceleration of cures, as the authors do, isn’t really anything new.

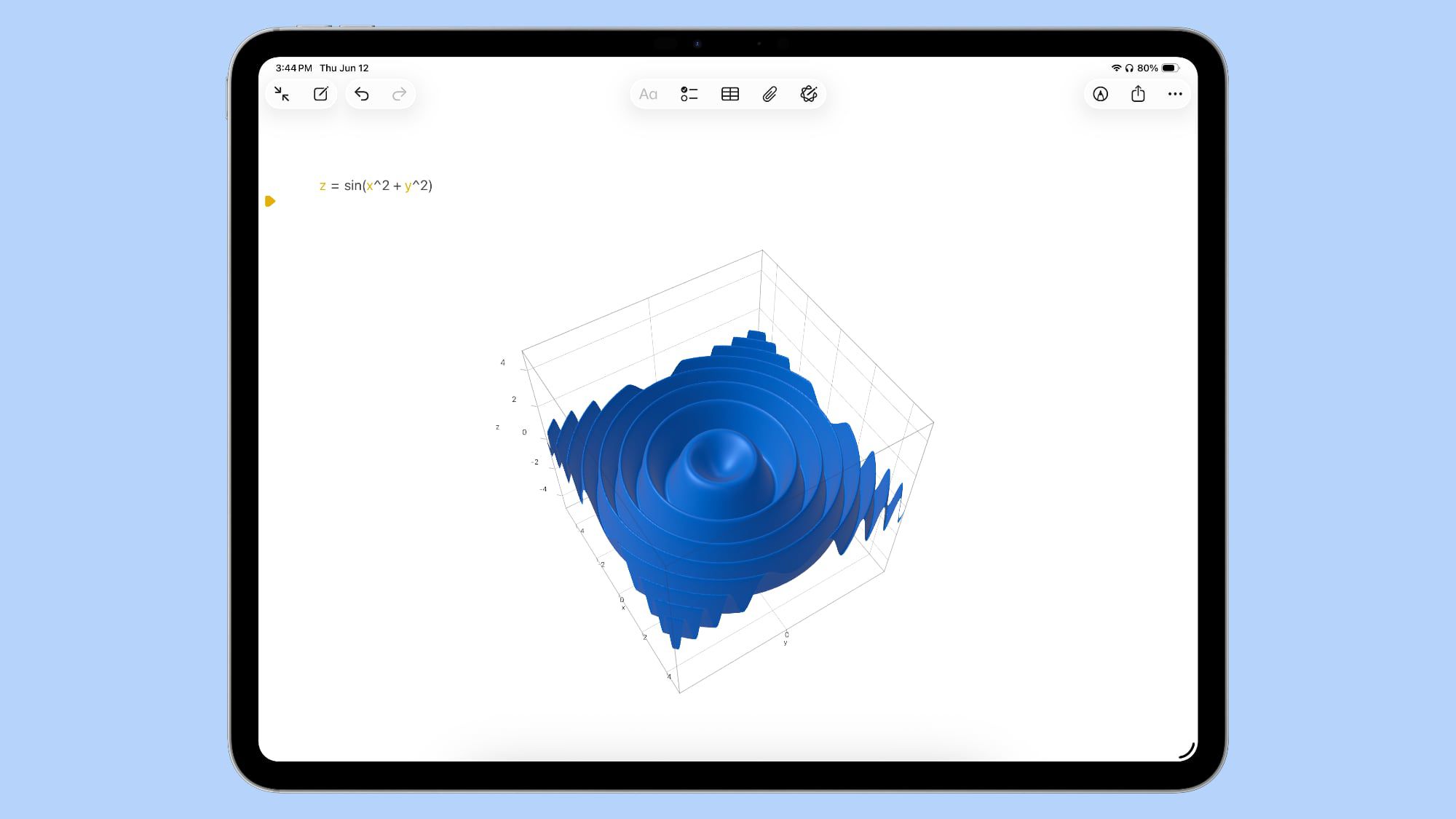

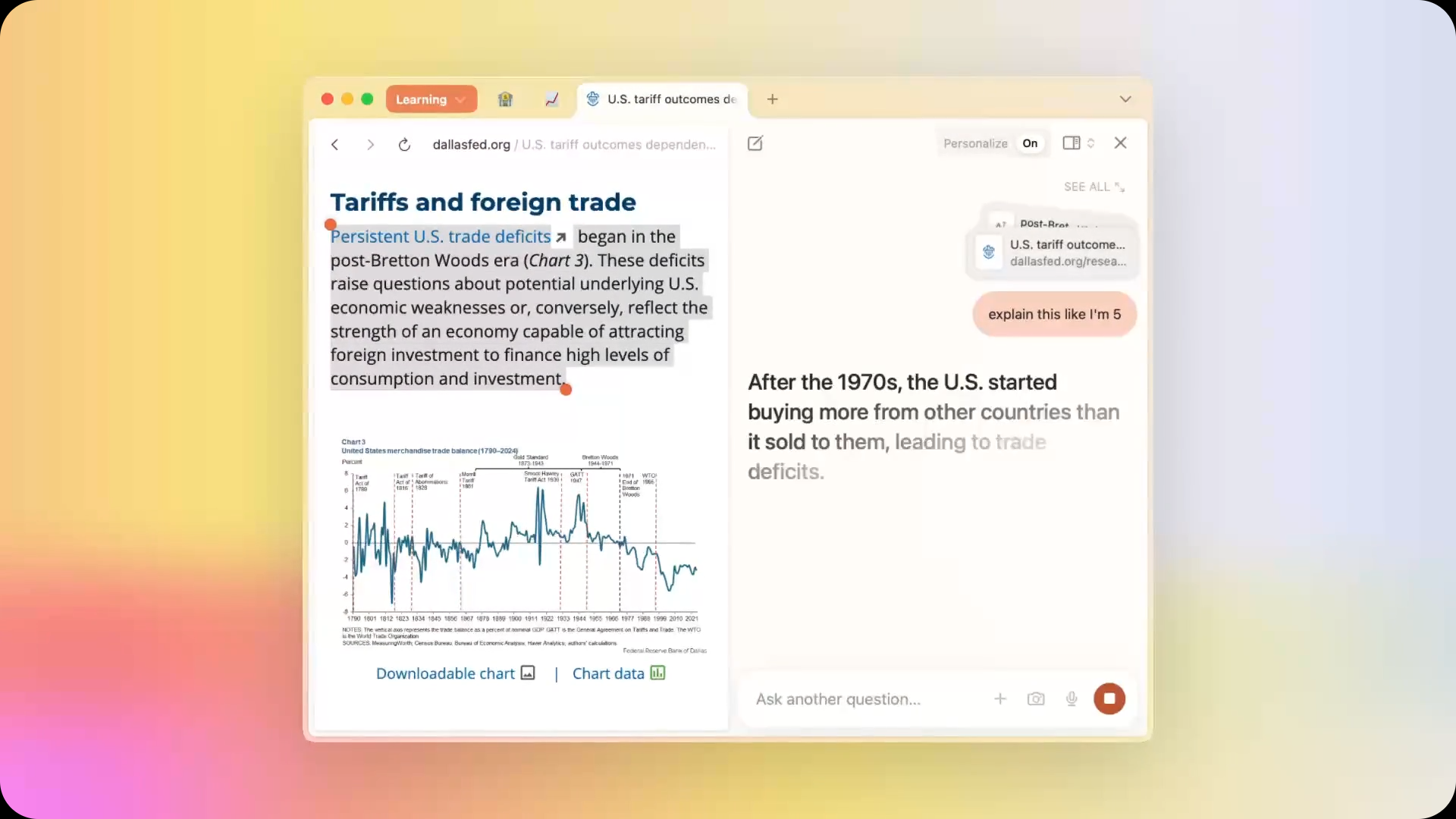

Makary and Prasad also list artificial intelligence as a priority—specifically, generative AI. They write that “on May 8, 2025, the agency implemented the first AI-assisted scientific review pilot using the latest generative AI technology.” It’s not clear exactly which technology was used, or how. But this priority didn’t surprise Rachel Sachs, a professor of health law at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Both this administration and the previous administration were very interested in the use of AI technologies,” she says. She points out that as of last year, the FDA had already approved over a thousand medical devices that make use of AI and machine learning. And the agency has also been considering how it might use the technologies in its review process, she adds: “It’s not a new idea.”

There’s another sticking point. Writing a list of priorities in JAMA is one thing. Implementing them amid hugely disruptive and damaging cuts underway across federal health and science agencies is quite another.

Makary and Prasad have both made claims to the effect that they support “gold standard” science and have built their careers on extolling the virtues of evidence-based medicine. But it’s hard to square this position with the actions of the administration, including the huge budget cuts made to the National Institutes of Health, restrictions on government-funded research, and mass layoffs across multiple government health agencies, including the FDA. “It’s almost as if the two sides are talking past each other,” says Sachs.

As a result, it’s impossible to predict exactly what’s going to happen. We’ll have to wait to see how this all pans out.

This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.

![Apple Shares Teaser Trailer for 'The Lost Bus' Starring Matthew McConaughey [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97582/97582/97582-640.jpg)

_Marek_Uliasz_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![Top Features of Vision-Based Workplace Safety Tools [2025]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/379e66_7e75a4bcefe14e4fbc100abdff83bed3~mv2.jpg/v1/fit/w_1000,h_884,al_c,q_80/file.png?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 152]: ChatGPT Connectors, AI-Human Relationships, New AI Job Data, OpenAI Court-Ordered to Keep ChatGPT Logs & WPP’s Large Marketing Model](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20152%20cover.png)

![[DEALS] Microsoft Visual Studio Professional 2022 + The Premium Learn to Code Certification Bundle (97% off) & Other Deals Up To 98% Off](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

.jpg?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-35-45-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

-30-7-screenshot_0FxoE4J.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)