How Supercritical CO2 Working Fluid Can Increase Power Plant Efficiency

Using steam to produce electricity or perform work via steam turbines has been a thing for a very long time. Today it is still exceedingly common to use steam in …read more

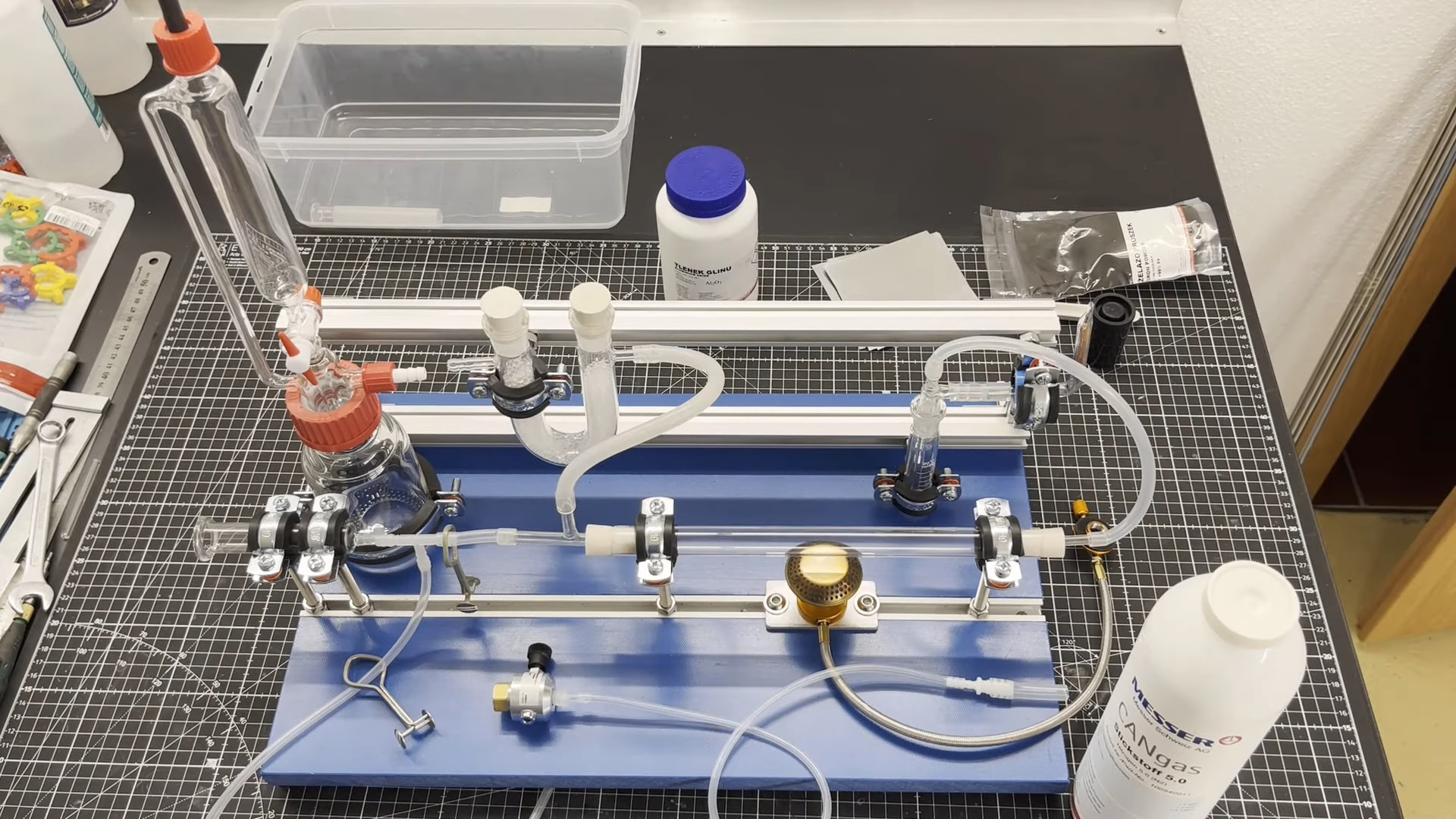

Using steam to produce electricity or perform work via steam turbines has been a thing for a very long time. Today it is still exceedingly common to use steam in this manner, with said steam generated either by burning something (e.g. coal, wood), by using spicy rocks (nuclear fission) or from stored thermal energy (e.g. molten salt). That said, today we don’t use steam in the same way any more as in the 19th century, with e.g. supercritical and pressurized loops allowing for far higher efficiencies. As covered in a recent video by [Ryan Inis], a more recent alternative to using water is supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2), which could boost the thermal efficiency even further.

In the video [Ryan Inis] goes over the basics of what the supercritical fluid state of CO2 is, which occurs once the critical point is reached at 31°C and 83.8 bar (8.38 MPa). When used as a working fluid in a thermal power plant, this offers a number of potential advantages, such as the higher density requiring smaller turbine blades, and the potential for higher heat extraction. This is also seen with e.g. the shift from boiling to pressurized water loops in BWR & PWR nuclear plants, and in gas- and salt-cooled reactors that can reach far higher efficiencies, as in e.g. the HTR-PM and MSRs.

In a 2019 article in Power goes over some of the details, including the different power cycles using this supercritical fluid, such as various Brayton cycles (some with extra energy recovery) and the Allam cycle. Of course, there is no such thing as a free lunch, with corrosion issues still being worked out, and despite the claims made in the video, erosion is also an issue with supercritical CO2 as working fluid. That said, it’s in many ways less of an engineering issue than supercritical steam generators due to the far more extreme critical point parameters of water.

If these issues can be overcome, it could provide some interesting efficiency boosts for thermal plants, with the caveat that likely nobody is going to retrofit existing plants, supercritical steam (coal) plants already exist and new nuclear plant designs are increasingly moving towards gas, salt and even liquid metal coolants, though secondary coolant loops (following the typical steam generator) could conceivably use CO2 instead of water where appropriate.

![Mike Rockwell is Overhauling Siri's Leadership Team [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97096/97096/97096-640.jpg)

![Instagram Releases 'Edits' Video Creation App [Download]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97097/97097/97097-640.jpg)

![Hands-On With 'iPhone 17 Air' Dummy Reveals 'Scary Thin' Design [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97100/97100/97100-640.jpg)

![Inside Netflix's Rebuild of the Amsterdam Apple Store for 'iHostage' [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97095/97095/97095-640.jpg)

![What iPhone 17 model are you most excited to see? [Poll]](https://9to5mac.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2025/04/iphone-17-pro-sky-blue.jpg?quality=82&strip=all&w=290&h=145&crop=1)

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

![BPMN-procesmodellering [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/l7l8q49F.png)

-All-will-be-revealed-00-35-05.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)