How the federal government is tracking changes in the supply of street drugs

In 2021, the Maryland Department of Health and the state police were confronting a crisis: Fatal drug overdoses in the state were at an all-time high, and authorities didn’t know why. There was a general sense that it had something to do with changes in the supply of illicit drugs—and specifically of the synthetic opioid…

In 2021, the Maryland Department of Health and the state police were confronting a crisis: Fatal drug overdoses in the state were at an all-time high, and authorities didn’t know why. There was a general sense that it had something to do with changes in the supply of illicit drugs—and specifically of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has caused overdose deaths in the US to roughly double over the past decade, to more than 100,000 per year.

But Maryland officials were flying blind when it came to understanding these fluctuations in anything close to real time. The US Drug Enforcement Administration reported on the purity of drugs recovered in enforcement operations, but the DEA’s data offered limited detail and typically came back six to nine months after the seizures. By then, the actual drugs on the street had morphed many times over. Part of the investigative challenge was that fentanyl can be some 50 times more potent than heroin, and inhaling even a small amount can be deadly. This made conventional methods of analysis, which required handling the contents of drug packages directly, incredibly risky.

Seeking answers, Maryland officials turned to scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the national metrology institute for the United States, which defines and maintains standards of measurement essential to a wide range of industrial sectors and health and security applications.

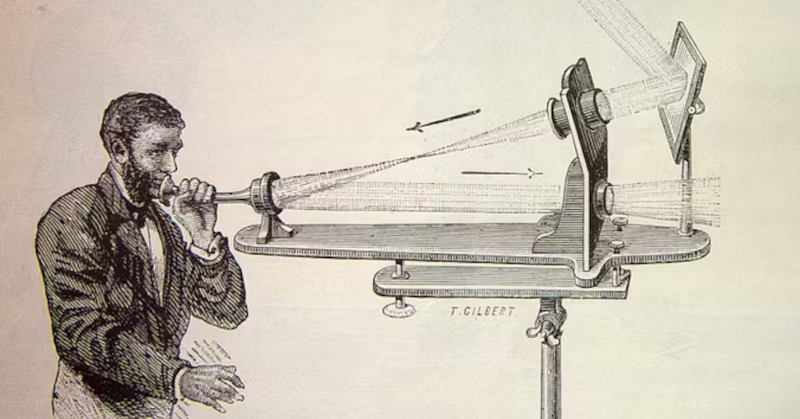

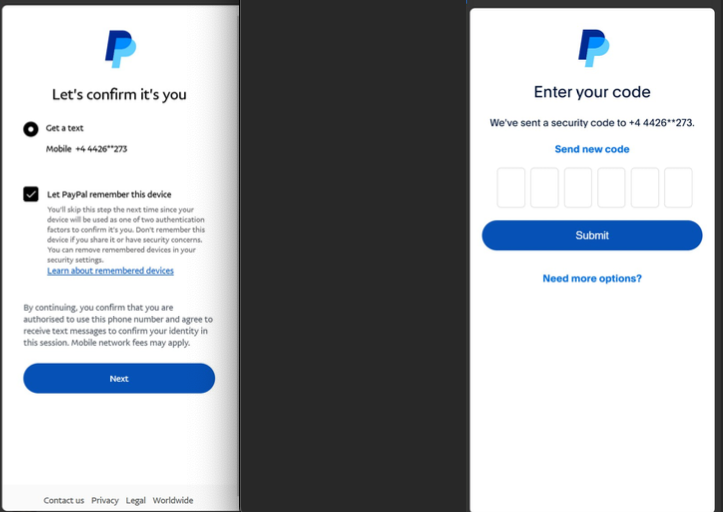

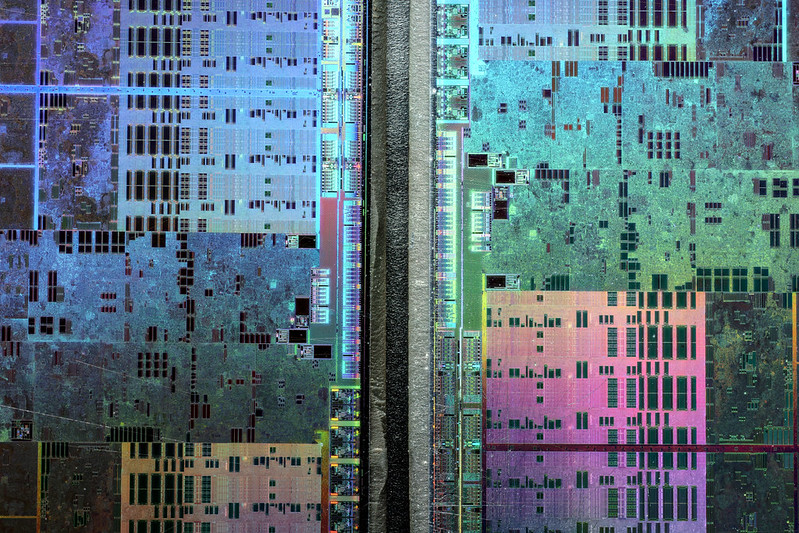

There, a research chemist named Ed Sisco and his team had developed methods for detecting trace amounts of drugs, explosives, and other dangerous materials—techniques that could protect law enforcement officials and others who had to collect these samples. Essentially, Sisco’s lab had fine-tuned a technology called DART (for “direct analysis in real time”) mass spectrometry—which the US Transportation Security Administration uses to test for explosives by swiping your hand—to enable the detection of even tiny traces of chemicals collected from an investigation site. This meant that nobody had to open a bag or handle unidentified powders; a usable residue sample could be obtained by simply swiping the outside of the bag.

Sisco realized that first responders or volunteers at needle exchange sites could use these same methods to safely collect drug residue from bags, drug paraphernalia, or used test strips—which also meant they would no longer need to wait for law enforcement to seize drugs for testing. They could then safely mail the samples to NIST’s lab in Maryland and get results back in as little as 24 hours, thanks to innovations in Sisco’s lab that shaved the time to generate a complete report from 10 to 30 minutes to just one or two. This was partly enabled by algorithms that allowed them to skip the time-consuming step of separating the compounds in a sample before running an analysis.

The Rapid Drug Analysis and Research (RaDAR) program launched as a pilot in October 2021 and uncovered new, critical information almost immediately. Early analysis found xylazine—a veterinary sedative that’s been associated with gruesome wounds in users—in about 80% of opioid samples they collected.

This was a significant finding, Sisco says: “Forensic labs care about things that are illegal, not things that are not illegal but do potentially cause harm. Xylazine is not a scheduled compound, but it leads to wounds that can lead to amputation, and it makes the other drugs more dangerous.” In addition to the compounds that are known to appear in high concentrations in street drugs—xylazine, fentanyl, and the veterinary sedative medetomidine—NIST’s technology can pick out trace amounts of dozens of adulterants that swirl through the street-drug supply and can make it more dangerous, including acetaminophen, rat poison, and local anesthetics like lidocaine. What’s more, the exact chemical formulation of fentanyl on the street is always changing, and differences in molecular structure can make the drugs deadlier. So Sisco’s team has developed new methods for spotting these “analogues”—compounds that resemble known chemical structures of fentanyl and related drugs.

The RaDAR program has expanded to work with partners in public health, city and state law enforcement, forensic science, and customs agencies at about 65 sites in 14 states. Sisco’s lab processes 700 to 1,000 samples a month. About 85% come from public health organizations that focus on harm reduction (an approach to minimizing negative impacts of drug use for people who are not ready to quit). Results are shared at these collection points, which also collect survey data about the effects of the drugs.

Jason Bienert, a wound-care nurse at Johns Hopkins who formerly volunteered with a nonprofit harm reduction organization in rural northern Maryland, started participating in the RaDAR program in spring 2024. “Xylazine hit like a storm here,” he says. “Everyone I took care of wanted to know what was in their drugs because they wanted to know if there was xylazine in it.” When the data started coming back, he says, “it almost became a race to see how many samples we could collect.” Bienert sent in about 14 samples weekly and created a chart on a dry-erase board, with drugs identified by the logos on their bags, sorted into columns according to the compounds found in them: heroin, fentanyl, xylazine, and everything else.

“It was a super useful tool,” Bienert says. “Everyone accepted the validity of it.” As people came back to check on the results of testing, he was able to build rapport and offer additional support, including providing wound care for about 50 people a week.

The breadth and depth of testing under the RaDAR program allow an eagle’s-eye view of the national street-drug landscape—and insights about drug trafficking. “We’re seeing distinct fingerprints from different states,” says Sisco. NIST’s analysis shows that fentanyl has taken over the opioid market—except for pockets in the Southwest, there is very little heroin on the streets anymore. But the fentanyl supply varies dramatically as you cross the US. “If you drill down in the states,” says Sisco, “you also see different fingerprints in different areas.” Maryland, for example, has two distinct fentanyl supplies—one with xylazine and one without.

In summer 2024, RaDAR analysis detected something really unusual: the sudden appearance of an industrial-grade chemical called BTMPS, which is used to preserve plastic, in drug samples nationwide. In the human body, BTMPS acts as a calcium channel blocker, which lowers blood pressure, and mixed with xylazine or medetomidine, can make overdoses harder to treat. Exactly why and how BTMPS showed up in the drug supply isn’t clear, but it continues to be found in fentanyl samples at a sustained level since it was initially detected. “This was an example of a compound we would have never thought to look for,” says Sisco.

To Sisco, Bienert, and others working on the public health front of the drug crisis, the ever-shifting chemical composition of the street-drug supply speaks to the futility of the “war on drugs.” They point out that a crackdown on heroin smuggling is what gave rise to fentanyl. And NIST’s data shows how in June 2024—the month after Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro signed a bill to make possession of xylazine illegal in his state—it was almost entirely replaced on the East Coast by the next veterinary drug, medetomidine.

Over the past year, for reasons that are not fully understood, drug overdose deaths nationally have been falling for the first time in decades. One theory is that xylazine has longer-lasting effects than fentanyl, which means people using drugs are taking them less often. Or it could be that more and better information about the drugs themselves is helping people make safer decisions.

“It’s difficult to say the program prevents overdoses and saves lives,” says Sisco. “But it increases the likelihood of people coming in to needle exchange centers and getting more linkages to wound care, other services, other education.” Working with public health partners “has humanized this entire area for me,” he says. “There’s a lot more gray than you think—it’s not black and white. And it’s a matter of life or death for some of these people.”

Adam Bluestein writes about innovation in business, science, and technology.

![Apple to Split Enterprise and Western Europe Roles as VP Exits [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97032/97032/97032-640.jpg)

![Nanoleaf Announces New Pegboard Desk Dock With Dual-Sided Lighting [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97030/97030/97030-640.jpg)

![Apple's Foldable iPhone May Cost Between $2100 and $2300 [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97028/97028/97028-640.jpg)

.webp?#)

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)