Non-Transparency Resumed After Pirate Site Blacklist Publicly Exposed in Error

Since shutting down most pirate sites is impossible, Germany's ISPs are given a secret list of pirate domains to block, which in theory hides the existence of the pirate sites from internet users. After it emerged that a local ISP had accidentally exposed the list to the public for the last 10 months, the unintended transparency was quietly yet swiftly reversed. This response provides another point for debate as site-blocking proposals heat up in the United States. From: TF, for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

As debate heats up in the United States over proposed site-blocking legislation, opinions of what that might mean in practice are already beginning to emerge.

As debate heats up in the United States over proposed site-blocking legislation, opinions of what that might mean in practice are already beginning to emerge.

Introduced by Rep. Zoe Lofgren late January, the Foreign Anti-Digital Piracy Act (FADPA) attempts to distill well over a decade of site blocking experience amassed by U.S. rightsholders overseas, into a package carefully curated for use on home soil.

Site-Blocking Debate Returns to Polarization

Should it become law, FAPDA would allow rightsholders to obtain site blocking orders targeted at verified pirate sites, run by foreign or assumed foreign operators. The proposals as they stand today envision blocking orders that would apply to both ISPs and DNS resolvers, the latter an already controversial trend that has only recently shown momentum in Europe.

As proponents have made clear many times over the past 15 years or so, to remain effective site-blocking must continuously adapt. That necessarily means that the FADPA proposals on the table today are the starting point for U.S. site-blocking. For those advocating in favor of FADPA, especially as a highly predictable framework with guardrails for safety, the inherent need to adapt and expand presents challenges for longer-term assurances.

No Wild Predictions Required, Europe Holds the Answers

Unlike the SOPA debate in 2012, where wild predictions one way or another had no clear historical basis, today there is a deep well of information to draw from, much of it the result of U.S. rightsholders’ implementation of site-blocking in Europe. As such, events there should be considered informative.

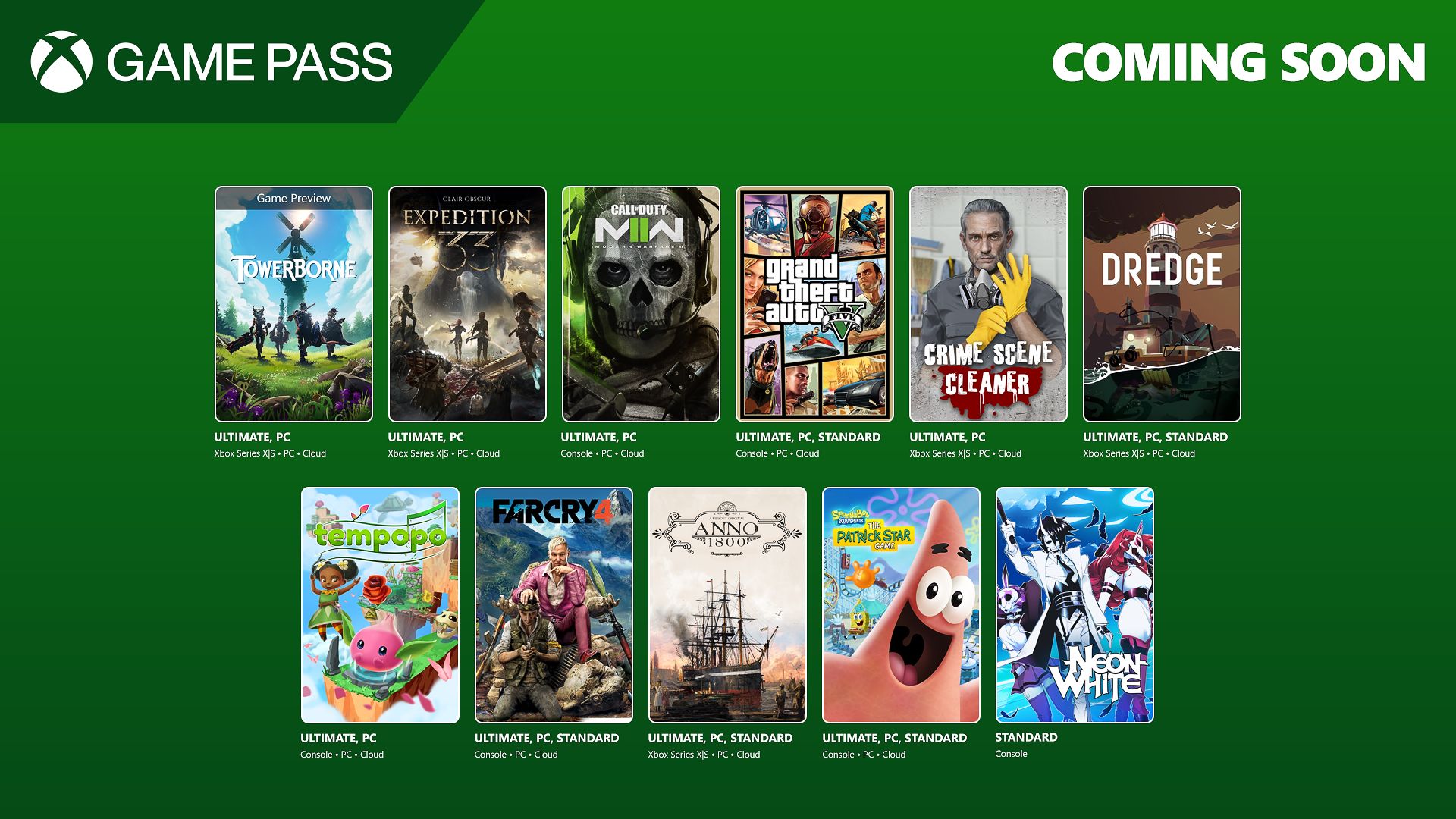

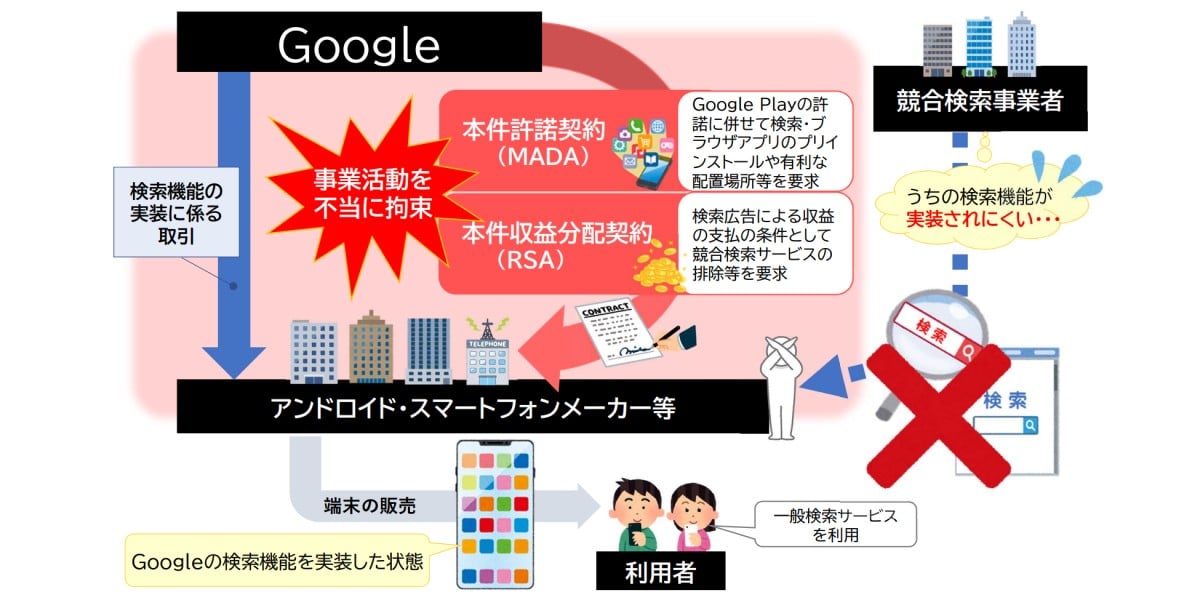

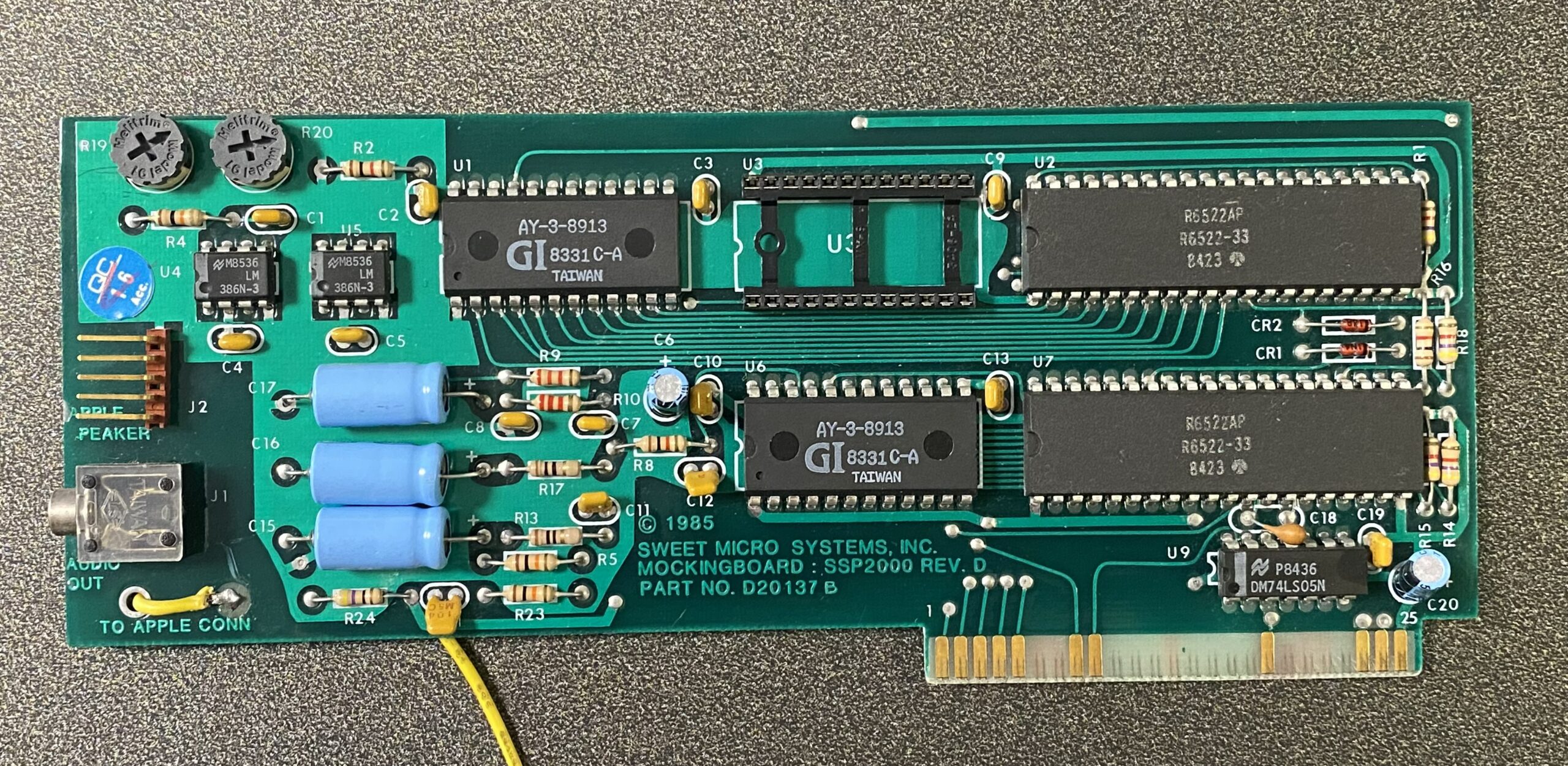

Established four years ago, Germany operates an administrative site blocking regime which requires no direct legal oversight. A partnership between rightsholders and local ISPs saw the launch of the “Clearing Body for Copyright on the Internet” (CUII) which is now responsible for handing down blocking instructions against sites that structurally infringe copyright.

Recommendations for blocking are published on the CUII website, along with redacted reports explaining investigators’ findings. The image below shows all recommendations for blocking since the program began.

This level of transparency is already a step up from broadly equivalent schemes seen elsewhere in Europe. However, in common with many of its counterparts elsewhere, the domains subsequently nominated by rightsholders and then blocked by ISPs are on a confidential list to which the public has no access. Or at least, that was the original plan.

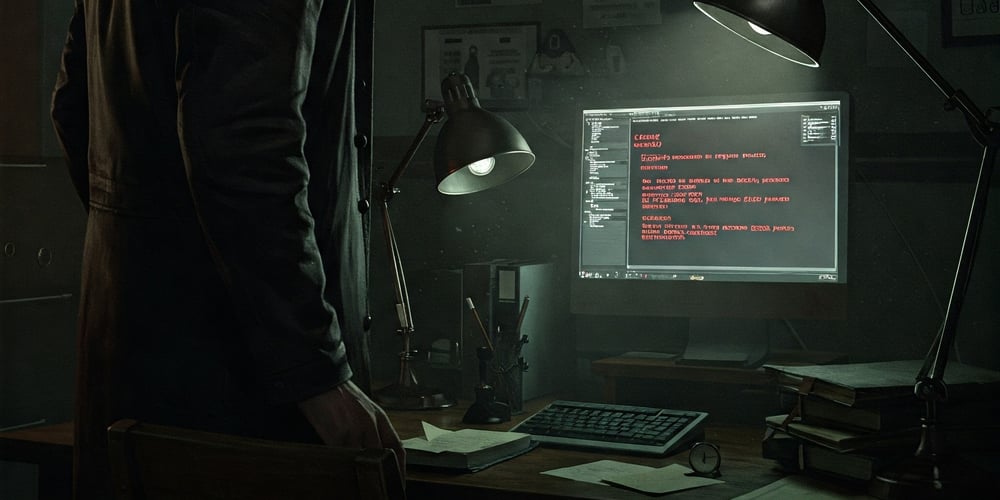

Confidential Block List Exposed By ISP

A Netzpolitik report published last week revealed that Germany’s secret site-blocking list had been publicly available for at least 10 months via the URL rpz01do.versatel-west.de. Accidentally made available by ISP 1&1 Versatel, the URL let visitors see every domain blocked by local ISPs, enabling them to see how the list changed over time following numerous updates.

While the CUII website lists 24 platforms for blocking, at last count the exposed list contained well over ten times more domains/subdomains, over 300 in total. For perspective, Germany’s site-blocking program is very modest when compared to schemes in the UK, France, Italy, and Spain, for example, where thousands of sites are blocked with information on domains mostly restricted.

Last year we reported on the work of Damian, a then-17-year-old in Germany who lifted the veil of secrecy on the scale of domain blocking via the site cuiiliste.de.

“CUII is a private organization that blocks websites that it believes violate copyright law – without any court orders. In addition, their approach seems very non-transparent in my opinion,” Damian said.

Damian and others working on the project used various DNS-based techniques to establish which domains were blocked in Germany. However, he informs Netzpolitik that access to the ‘leaked’ master list helped to confirm that all blocked domains were present on the cuiliste.de site, something that can longer be guaranteed.

That’s because, predictably, as soon as 1&1 Versatel discovered its accidental transparency, measures were swiftly taken to ensure the list was hidden away as originally intended.

Site-Blocking = Censorship?

A pro-FADPA article published late last week by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation put forward reasons ‘Why the US Should Block Piracy’. One of a series of articles with a similar theme over the last few years, the piece describes site-blocking as “a no-brainer” and U.S. policy as having “international precedent.”

The crux of the piece dismisses concerns that FADPA could be used as a tool for censorship, and rejects the notion that the “one sided process” through which orders are obtained are “fundamentally flawed.” These are entrenched positions that have closed very little over the last 12+ years and will undoubtedly continue to rage as the months unfold.

“[W]hen policymakers propose reasonable, legally sound tools to stop [piracy], critics respond with hyperbole, misdirection, and scare tactics,” the piece adds, a claim that has been utilized by both sides, if any at all.

No Censorship Where There’s Transparency

Claims of censorship often depend on the context and the FADPA proposals in the U.S. will need to address those claims at some point, whether justified or not. However, while censorship and transparency have some similarities, the latter may deserve more attention.

Proposals in the U.S. suggest a system not dissimilar to those operating in Europe, with and without involvement of the courts. An initial blocking order against a platform will be made available to the public, but since those orders are likely to be flexible (‘dynamic’ in site-blocking parlance), permission will be granted to block additional resources without returning to court.

Following the clear pattern on display in Europe, whatever rightsholders and ISPs agree to block privately, will be blocked, and if there is no transparency requirement, none will be forthcoming.

From: TF, for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

.webp?#)

![Apple to Split Enterprise and Western Europe Roles as VP Exits [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97032/97032/97032-640.jpg)

![Nanoleaf Announces New Pegboard Desk Dock With Dual-Sided Lighting [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97030/97030/97030-640.jpg)

![Apple's Foldable iPhone May Cost Between $2100 and $2300 [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97028/97028/97028-640.jpg)

![[The AI Show Episode 144]: ChatGPT’s New Memory, Shopify CEO’s Leaked “AI First” Memo, Google Cloud Next Releases, o3 and o4-mini Coming Soon & Llama 4’s Rocky Launch](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20144%20cover.png)