The elephant in the room for energy tech? Uncertainty.

At a conference dedicated to energy technology that I attended this week, I noticed an outward attitude of optimism and excitement. But it’s hard to miss the current of uncertainty just underneath. The ARPA-E Energy Innovation Summit, held this year just outside Washington, DC, gathers some of the most cutting-edge innovators working on everything from…

At a conference dedicated to energy technology that I attended this week, I noticed an outward attitude of optimism and excitement. But it’s hard to miss the current of uncertainty just underneath.

The ARPA-E Energy Innovation Summit, held this year just outside Washington, DC, gathers some of the most cutting-edge innovators working on everything from next-generation batteries to plants that can mine for metals. Researchers whose projects have received funding from ARPA-E—part of the US Department of Energy that gives money to high-risk research in energy—gather to show their results and mingle with each other, investors, and nosy journalists like yours truly. (For more on a few of the coolest things I saw, check out this story.)

This year, though, there was an elephant in the room, and it’s the current state of the US federal government. Or maybe it’s climate change? In any case, the vibes were weird.

The last time I was at this conference, two years ago, climate change was a constant refrain on stage and in conversations. The central question was undoubtedly: How do we decarbonize, generate energy, and run our lives without relying on polluting fossil fuels?

This time around, I didn’t hear the phrase “climate change” once during the opening session, including in speeches from US Secretary of Energy Chris Wright and acting ARPA-E Director Daniel Cunningham. The focus was on American energy dominance, on how we can get our hands on more, more, more energy to meet growing demand.

Last week, Wright spoke at an energy conference in Houston and had a lot to say about climate, calling climate change a “side effect of building the modern world” and climate policies irrational and quasi-religious, and he said that when it came to climate action, the cure had become worse than the disease.

I was anticipating similar talking points at the summit, but this week, climate change hardly got a mention.

What I noticed in Wright’s speech and in the choice of programming throughout the conference is that some technologies appear to be among the favored, and others are decidedly less prominent. Nuclear power and fusion were definitely on the “in” list. There was a nuclear panel in the opening session, and in his remarks Wright called out companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems and Zap Energy. He also praised small modular reactors.

Renewables, including wind and solar, were mentioned only in the context of their inconsistency—Wright dwelled on that, rather than on other facts I’d argue are just as important, like that they are among the cheapest methods of generating electricity today.

In any case, Wright seemed appropriately hyped about energy, given his role in the administration. “Call me biased, but I think there’s no more impactful place to work in than energy,” Wright said during his opening remarks on the first morning of the summit. He sang the praises of energy innovation, calling it a tool to drive progress, and outlined his long career in the field.

This all comes after a chaotic couple of months for the federal government that are undoubtedly affecting the industry. Mass layoffs have hit federal agencies, including the Department of Energy. President Donald Trump very quickly tried to freeze spending from the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes tax credits and other support for EVs and power plants.

As I walked around the showcase and chatted with experts over coffee, I heard a range of reactions to the opening session and feelings about this moment for the energy sector.

People working in industries the Trump administration seems to favor, like nuclear energy, tended to be more positive. Some in academia who rely on federal grants to fund their work were particularly nervous about what comes next. One researcher refused to talk to me when I said I was a journalist. In response to my questions about why they weren’t able to discuss the technology on display at their booth, another member on the same project said only that it’s a wild time.

Making progress on energy technology doesn’t require that we all agree on exactly why we’re doing it. But in a moment when we need all the low-carbon technologies we can get to address climate change—a problem scientists overwhelmingly agree is a threat to our planet—I find it frustrating that politics can create such a chilling effect in some sectors.

At the conference, I listened to smart researchers talk about their work. I saw fascinating products and demonstrations, and I’m still optimistic about where energy can go. But I also worry that uncertainty about the future of research and government support for emerging technologies will leave some valuable innovations in the dust.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

![Apple Reorganizes Executive Team to Rescue Siri [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96777/96777/96777-640.jpg)

![The latest vinyl Android figure is a faux wood ‘Pine Pal’ where no two are alike [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/03/android-figure-pine-pal-1.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

![[The AI Show Episode 139]: The Government Knows AGI Is Coming, Superintelligence Strategy, OpenAI’s $20,000 Per Month Agents & Top 100 Gen AI Apps](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20139%20cover-2.png)

![[The AI Show Episode 138]: Introducing GPT-4.5, Claude 3.7 Sonnet, Alexa+, Deep Research Now in ChatGPT Plus & How AI Is Disrupting Writing](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20138%20cover.png)

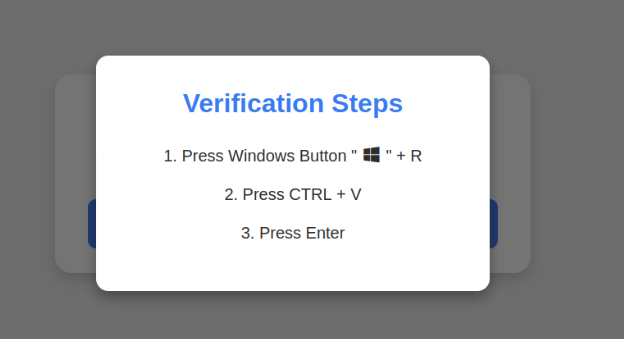

![What are good examples of 'preflight check patterns' on existing applications? [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/yl2Tr80w.png)

-Assassin's-Creed-Shadows-Review-00-12-31.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

![Release: Rendering Ranger: R² [Rewind]](https://images-3.gog-statics.com/48a9164e1467b7da3bb4ce148b93c2f92cac99bdaa9f96b00268427e797fc455.jpg)