Regression Discontinuity Design: How It Works and When to Use It

From core ideas to real-world analysis — how RDD causal inference works, how to run it, and how to get it right. The post Regression Discontinuity Design: How It Works and When to Use It appeared first on Towards Data Science.

Regression Discontinuity Design: How It Works and When to Use It

You’re an avid data scientist and experimenter. You know that randomisation is the summit of Mount Evidence Credibility, and you also know that when you can’t randomise, you resort to observational data and Causal Inference techniques. At your disposal are various methods for spinning up a control group — difference-in-differences, inverse propensity score weighting, and others. With an assumption here or there (some shakier than others), you estimate the causal effect and drive decision-making. But if you thought it couldn’t get more exciting than “vanilla” causal inference, read on.

Personally, I’ve often found myself in at least two scenarios where “just doing causal inference” wasn’t straightforward. The common denominator in these two scenarios? A missing control group — at first glance, that is.

First, the cold-start scenario: the company wants to break into an uncharted opportunity space. Often there is no experimental data to learn from, nor has there been any change (read: “exogenous shock”), from the business or product side, to leverage in the more common causal inference frameworks like difference-in-differences (and other cousins in the pre-post paradigm).

Second, the unfeasible randomisation scenario: the organisation is perfectly intentional about testing an idea, but randomisation is not feasible—or not even wanted. Even emulating a natural experiment might be constrained legally, technically, or commercially (especially when it’s about pricing), or when interference bias arises in the marketplace.

These situations open up the space for a “different” type of causal inference. Although the method we’ll focus on here is not the only one suited for the job, I’d love for you to tag along in this deep dive into Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD).

In this post, I’ll give you a crisp view of how and why RDD works. Inevitably, this will involve a bit of math — a pleasant sight for some — but I’ll do my best to keep it accessible with classic examples from the literature.

We’ll also see how RDD can tackle a thorny causal inference challenge in e-commerce and online marketplaces: the impact of listing position on listing performance. In this practical section we’ll cover key modelling considerations that practitioners often face: parametric versus non-parametric RDD, choosing the right bandwidth parameter, and more. So, grab yourself a cup of of coffee and let’s jump in!

Outline

- How and why RDD Works: Key Concepts

- RDD in Action: Search Ranking and listing performance Example

- Conclusion

How and why RDD works

Regression Discontinuity Design exploits cutoffs — thresholds — to recover the effect of a treatment on an outcome. More precisely, it looks for a sharp change in the probability of treatment assignment on a ‘running’ variable. If treatment assignment depends solely on the running variable, and the cutoff is arbitrary, i.e. exogenous, then we can treat the units around it as randomly assigned. The difference in outcomes just above and below the cutoff gives us the causal effect.

For example, a scholarship awarded only to students scoring above 90, creates a cutoff based on test scores. That the cutoff is 90 is arbitrary — it could have been 80 for that matter; the line had just to be drawn somewhere. Moreover, scoring 91 vs. 89 makes the whole difference as for the treatment: either you get it or not. But regarding capability, the two groups of students that scored 91 and 89 are not really different, are they? And those who scored 89.9 versus 90.1 — if you insist?

Making the cutoff could come down to randomness, when it’s just a bout a few points. Maybe the student drank too much coffee right before the test — or too little. Maybe they got bad news the night before, were thrown off by the weather, or anxiety hit at the worst possible moment. It’s this randomness that makes the cutoff so instrumental in RDD.

Without a cutoff, you don’t have an RDD — just a scatterplot and a dream. But, the cutoff by itself is not equipped with all it takes to identify the causal effect. Why it works hinges on one core identification assumption: continuity.

The continuity assumption, and parallel worlds

If the cutoff is the cornerstone of the technique, then its importance comes entirely from the continuity assumption. The idea is a simple, counterfactual one: had there been no treatment, then there would’ve been no effect.

To ground the idea of continuity, let’s jump straight into a classic example from public health: does legal alcohol access increase mortality?

Imagine two worlds where everyone and everything is the same. Except for one thing: a law that sets the minimum legal drinking age at 18 years (we’re in Europe, folks).

In the world with the law (the factual world), we’d expect alcohol consumption to jump right after age 18. Alcohol-related deaths should jump too, if there is a link.

Now, take the counterfactual world where there is no such law; there should be no such jump. Alcohol consumption and mortality would likely follow a smooth trend across age groups.

Now, that’s a good thing for identifying the causal effect; the absence of a jump in deaths in the counterfactual world is the necessary condition to interpret a jump in the factual world as the impact of the law.

Put simply: if there is no treatment, there shouldn’t be a jump in deaths. If there is, then something other than our treatment is causing it, and the RDD is not valid.

The continuity assumption can be written in the potential outcomes framework as:

\begin{equation}

\lim_{x \to c^-} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x] = \lim_{x \to c^+} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x]

\label{eq: continuity_po}

\end{equation}

Where \(Y_i(0)\) is the potential outcome, say, risk of death of subject \(/mathbb{i}\) under no treatment.

Notice that the right-hand side is a quantity of the counterfactual world; not one that can be observed in the factual world, where subjects are treated if they fall above the cutoff.

Unfortunately for us, we only have access to the factual world, so the assumption cannot be tested directly. But, luckily, we can proxy it. We will see placebo groups achieve this later in the post. But first, we start by identifying what can break the assumption:

- Confounders: something other than the treatment happens at the cutoff that also impacts the outcome. For instance, adolescents resorting to alcohol to alleviate the crushing pressure of being an adult now — something that has nothing to do with the law on the minimum age to consume alcohol (in the no-law world), but that does confound the effect we are after, happening at the same age — the cutoff, that is.

- Manipulating the running variable:

When units can influence their position with regard to the cutoff, it may be that units who did so are inherently different from those who did not. Hence, cutoff manipulation can result in selection bias: a form of confounding. Especially if treatment assignment is binding, subjects may try their best to get one version of the treatment over the other.

Hopefully, it’s clear what constitutes a RDD: the running variable, the cutoff, and most importantly, reasonable grounds to defend that continuity holds. With that, you’ve gotten yourself a neat and effective causal inference design for questions that can’t be answered by an A/B test, nor by some of the more common causal inference techniques like diff-in-diff, nor with stratification.

In the next section, we continue shaping our understanding of how RDD works; how does RDD “control” confounding relationships? What exactly does it estimate? Can we not just control for the running variable too? These are questions that we tackle next.

RDD and instruments

If you are already familiar with instrumental variables (IV), you may see the similarities: both RDD and IV leverage an exogenous variable that does not cause the outcome directly, but does influence the treatment assignment, which in turn may influence the outcome. In IV this is a third variable Z; in RDD it’s the running variable that serves as an instrument.

Wait. A third variable; maybe. But an exogenous one? That’s less clear.

In our example of alcohol consumption, it is not hard to imagine that age — the running variable — is a confounder. As age increases, so might tolerance for alcohol, and with it the level of consumption. That’s a stretch, maybe, but not implausible.

Since treatment (legal minimum age) depends on age — only units above 18 are treated — treated and untreated units are inherently different. If age also influences the outcome, through a mechanism like the one sketched above, we got ourselves an apex confounder.

Still, the running variable plays a key role. To understand why, we need to look at how RDD and instruments leverage the frontdoor criterion to identify causal effects.

Backdoor vs. frontdoor

Perhaps almost instinctively, one may answer with controlling for the running variable; that’s what stratification taught us. The running variable is confounder, so we include it in our regression, and close the backdoor. But doing so would cause some trouble.

Remember, treatment assignment depends on the running variable so that everyone above the cutoff is treated with all certainty, and certainly not below it. So, if we control for the running variable, we run into two very related problems:

- Violation of the Positivity assumption: this assumption says that treated units should have a non-zero probability to receive the opposite treatment, and vice versa. Intuitively, conditioning on the running variable is like saying: “Let’s estimate the effect of being above the minimum age for alcohol consumption, while holding age fixed at 14.” That does not make sense. At any given value of running variable, treatment is either always 1 or always 0. So, there’s no variation in treatment conditional on the running variable to support such a question.

- Perfect collinearity at the cutoff: in estimating the treatment effect, the model has no way to separate the effect of crossing the cutoff from the effect of being at a particular value of X. The result? No estimate, or a forcefully dropped variable from the model design matrix. Singular design matrix, does not have full rank, these should sound familiar to most practitioners.

So no — conditioning on the running variable doesn’t make the running variable the exogenous instrument that we’re after. Instead, the running variable becomes exogenous by pushing it to the limit—quite literally. There where the running variable approaches the cutoff from either side, the units are the same with respect to the running variable. Yet, falling just above or below makes the difference as for getting treated or not. This makes the running variable a valid instrument, if treatment assignment is the only thing that happens at the cutoff. Judea Pearl refers to instruments as meeting the front-door criterion.

LATE, not ATE

So, in essence, we’re controlling for the running variable — but only near the cutoff. That’s why RDD identifies the local average treatment effect (LATE), a special flavour of the average treatment effect (ATE). The LATE looks like:

$$\delta_{SRD}=E\big[Y^1_i – Y_i^0\mid X_i=c_0]$$

The local bit refers to the partial scope of the population we are estimating the ATE for, which is the subpopulation around the cutoff. In fact, the further away the data point is from the cutoff, the more the running variable acts as a confounder, working against the RDD instead of in its favour.

Back to the context of the minimum age for legal alcohol consumption example. Adolescents who are 17 years and 11 months old are really not so different from those that are 18 years and 1 month old, on average. If anything, a month or two difference in age is not going to be what sets them apart. Isn’t that the essence of conditioning on, or holding a variable constant? What sets them apart is that the latter group can consume alcohol legally for being above the cutoff, and not the former.

This setup enables us to estimate the LATE for the units around the cutoff and with that, the effect of the minimum age policy on alcohol-related deaths.

We’ve seen how the continuity assumption has to hold to make the cutoff an interesting point along the running variable in identifying the causal effect of a treatment on the outcome. Namely, by letting the jump in the outcome variable be entirely attributable to the treatment. If continuity holds, the treatment is as-good-as-random near the cutoff, allowing us to estimate the local average treatment effect.

In the next section, we’ll walk through the practical setup of a real-world RDD: we identify the key concepts; the running variable and cutoff, treatment, outcome, covariates, and finally, we estimate the RDD after discussing some crucial modelling choices, and end the section with a placebo test.

RDD in Action: Search Ranking and listing performance Example

In e-commerce and online marketplaces, the starting point of the buyer experience is searching for a listing. Think of the visitor typing “Nikon F3 analogue camera” in the search bar. Upon carrying out this action, algorithms frantically sort through the inventory looking for the best matching listings to populate the search results page.

Time and attention are two scarce resources. So, it is in the interest of everyone involved — the buyer, the seller and the platform — to reserve the most prominent positions on the page for the matches with the highest anticipated chance to become successful trades.

Additionally, position effects in consumer behaviour suggest that users infer higher credibility and desirability from items “ranked” at the top. Think about high-tier products being placed at eye-height or above in supermarkets, and highlighted items on an e-commerce platform, at the top of the homepage.

So, the question then becomes: how does positioning on the search results page influence a listing’s chances to be sold?

Hypothesis: As with any good hypothesis, we need a bit of theory to ground it. Good for us is that we are not trying to find the cure for cancer. Our theory is about well-understood psychological phenomena and behavioural patterns, to put it overly sophisticated.

Think of primacy effect, anchoring bias and the resource theory of attention. These are well ideas in behavioural and cognitive psychology that back up our plan here.

Kicking off the conversation with a product manager will be more fun this way. Personally, I also get excited when I have to brush up on some psychology.

But I’ve found through and through that a theory is really secondary to any initiative in my industry (tech). Except for a research team and project, arguably. And it’s fair to say it helps us stay on-purpose: what we are doing is to bring business forward, not mother science.

If a listing is ranked higher on the search results page, then it will have a higher chance of being sold, because higher-ranked listings get more visibility and attention from users.

Intermezzo: business or theory?

Knowing the answer has real business value. Product and commercial teams could use it to design new paid features that help sellers get their listings on higher positions — a win for both the business and the user. It could also clarify the value of on-site real estate like banner positions and ad slots, helping drive growth in B2B advertising.

The question is about incrementality: would’ve listing \(\mathbb{j}\) been sold, had it been ranked 1st on the results page, instead of 15th. So, we want to make a causal statement. That’s hard for at least two reasons:

- A/B testing comes with a price, and;

- there are confounders we need to deal with if we resort to observational methods.

Let’s expand on that.

The cost of A/B testing

One experiment design could randomise the fetched listings across the page slots, independent of the listing relevance. Breaking the inherent link between relevance and position, we would learn the effect of position on listing performance. It’s an interesting idea — but a costly one.

While it’s a reasonable design for statistical inference, this setup is kind of terrible for the user and business. The user might have found what they needed—maybe even made a purchase. But instead, maybe half of the inventory they would have seen was remotely a good match because of our experiment. This suboptimal user experience likely hurts engagement in both the short and long term — especially for new users who are still to see what value the platform holds for them.

Can we think of a way to mitigate this loss? Still committed to A/B testing, one could expose a smaller set of users to the experiment. While it will scale down the consequences, it may also stand in the way of reaching sufficient statistical power by lowering the sample size. Moreover, even small audiences can be responsible for substantial revenue for some companies still — those with millions of users. So, cutting the exposed audience is not a silver bullet either.

Naturally, the way to go is to leave the platform and its users undisturbed — and still find a way to answer the question at hand. Causal inference is the right mindset for this, but the question is: how do we do that exactly?

Confounders

Listings don’t just make it to the top of the page on a good day; it’s their quality, relevance, and the sellers’ reputation that promote the ranking of a listing. Let’s call these three variables W.

What makes W tricky is that it influences both the ranking of the listing and also the probability that the listing gets clicked, a proxy for performance.

In other words, W affects both our treatment (position) and outcome (click), helping itself with the status of confounder.

Therefore, our task is to find a design that’s fit for purpose; one that effectively controls the confounding effect of W.

You don’t choose regression discontinuity — it chooses you

Not all causal inference designs are just sitting around waiting to be picked. Sometimes they show up when you least need them, and sometimes you get lucky when you need them most — like today.

It looks like we can use the page cutoff to identify the causal impact of position on clicks-through rate.

Abrupt cutoff in search results pagination

Let’s unpack the listing recommendation mechanism to see exactly how. Here’s what happens under the hood when a results page is generated for a search:

- Fetch listings matching the query

A coarse set of listings is pulled from the inventory, based on filters like location, radius, and category, etc. - Score listings on personal relevance

This step uses user history and listing quality proxies to predict what the user is most likely to click. - Rank listings by score

Higher scores get higher ranks. Business rules mix in ads and commercial content with organic results. - Populate pages

Listings are slotted by absolute relevance score. A results page ends at the kth listing, so the k+1th listing appears at the top of the next page. This is is going to be crucial to our design. - Impressions and user interaction

Users see the results in order of relevance. If a listing catches their eye, they might click and view more details: one step closer to the trade.

Practical setup and variables

So, what is exactly our design? Next, we walk through the reasoning and identification of the key ingredients of our design.

The running variable

In our setup, the running variable is the relevance score \(s_j\) for listing j. This score is a continuous, complex function of both user and listing properties:

$$s_j = f(u_i, l_j)$$

The listing’s rank \(r_j\) is simply a rank transformation of \(s_j\), defined as:

$$r_i = \sum_{j=1}^{n} \mathbf{1}(s_j \leq s_i)$$

Practically speaking, this means that for analytic purposes—such as fitting models, making local comparisons, or identifying cutoff points—knowing a listing’s rank conveys nearly the same information as knowing its underlying relevance score, and vice versa.

The relevance score \(s_j\) reflects how well a listing matches a specific user’s query, given parameters like location, price range, and other filters. But this score is relative—it only has meaning within the context of the listings returned for that particular search.

In contrast, rank (or position) is absolute. It directly determines a listing’s visibility. I think of rank as a standardising transformation of \(s_j\). For example, Listing A in search Z might have the highest score of 5.66, while Listing B in search K tops out at 0.99. These raw scores aren’t comparable across searches—but both listings are ranked first in their respective result sets. That makes them equivalent in terms of what really matters here: how visible they are to users.

Details: Relevance score vs. rank

The cutoff, and treatment

If a listing just misses the first page, it doesn’t fall to the bottom of page two — it is artificially bumped to the top. That’s a lucky break. Normally, only the most relevant listings appear at the top, but here a listing of merely moderate relevance ends up in a prime slot —albeit on the second page — purely due to the arbitrary position of the page break. Formally, the treatment assignment \(D_j\) goes like:

$$D_j = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } r_j > 30 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}$$

(Note on global rank: Rank 31 isn’t just the first listing on page two; it is still the 31st listing overall)

The strength of this setup lies in what happens near the cutoff: a listing ranked 30 may be nearly identical in relevance to one ranked 31. A small scoring fluctuation — or a high-ranking outlier — can push a listing over the threshold, flipping its treatment status. This local randomness is what makes the setup valid for RDD.

The outcome: Impression-to-click

Finally, we operationalise the outcome of interest as the click-though rate from impressions to clicks. Remember that all listings are ‘impressed’ when when the page is populated. The click is the binary indicator of the desired user behaviour.

In summary, this is our setup:

- Outcome: impression-to-click conversion

- Treatment: Landing on the first vs. second page

- Running variable: listing rank; page cutoff at 30

Next we walk through how to estimate the RDD.

Estimating RDD

In this section, we’ll estimate the causal parameter, interpret it, and connect them back to our core hypothesis: how position affects listing visibility.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

- Meet the data: Intro to the dataset

- Covariates: Why and how to include them

- Modelling choices: parametric RDD vs. not. Choosing the polynomial degree and bandwidth.

- Placebo-testing

- Density continuity testing

Meet the data

We’re working with impressions data from one of Adevinta’s (ex-eBay Classifieds Group) marketplaces. It’s real data, which makes the whole exercise feel grounded. That said, values and relationships are censored and scrambled where necessary to protect its strategic value.

An important note to how we interpret the RDD estimates and drive decisions, is how the data was collected: only those searches where the user saw both the first and second page were included.

This way, we partial out the page fixed effect if any, but the reality is that many users don’t make it to the second page at all. So there is a big volume gap. We discuss the repercussion in the analysis recap.

The dataset consists of these variables:

- Clicked: 1 if the listing was clicked, 0 otherwise – binary

- Position: the rank of the listing – numeric

- D: treatment indicator, 1 if position > 30, 0 otherwise – binary

- Category: product category of the listing – nominal

- Organic: 1 if organic, 0 if from a professional seller – binary

- Boosted: 1 if was paid to be at the top, 0 otherwise – binary

| click | rel_position | D | category | organic | boosted |

| 1 | -3 | 0 | A | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | -14 | 0 | A | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 3 | 1 | C | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 10 | 1 | D | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | -1 | 0 | K | 1 | 1 |

Covariates: how to include them to increase accuracy?

The running variable, the cutoff, and the continuity assumption, give you all you need to identify the causal effect. But including covariates can sharpen the estimator by reducing variance — if done right. And, oh is it easy to do it wrong.

The easiest thing to “break” about the RDD design, is the continuity assumption. Simultaneously, that’s the last thing we want to break (I already rambled long enough about this).

Therefore, the main quest in adding covariates is to it in such way that we reduce variance, while keeping the continuity assumption intact. One way to formulate that, is to assume continuity without covariates and with covariates:

\begin{equation}

\lim_{x \to c^-} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x] = \lim_{x \to c^+} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x] \text{(no covariates)}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lim_{x \to c^-} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x, Z_i] = \lim_{x \to c^+} \mathbb{E}[Y_i(0) \mid X_i = x, Z_i] \text{(covariates)}

\end{equation}

Where \(Z_i\) is a vector of covariates, for subject i. Less mathy, two things should remain unchanged after adding covariates:

- The functional form of the running variable, and;

- The (absence of the) jump in treatment assignment at the cutoff

I did not find out the above myself; Calonico, Cattaneo, Farrell, and Titiunik (2018) did. They developed a formal framework for incorporating covariates into RDD. I’ll leave the details to the paper. For now, some modelling guidelines can keep us going:

- Model covariates linearly so that the treatment effect remains the same with and without covariates, thanks to a simple and smooth partial effect of the covariates;

- Keep the model terms additive, so that the treatment effect remains the LATE, and does not become conditional on covariates (CATE); and to avoid adding a jump at the cutoff.

- The above implies that there be no interactions with the treatment indicator, nor with the running variable. Doing any of these may break continuity and invalidate our RDD design.

Our target model may look like this:

\begin{equation}

Y_i = \alpha + \tau D_i + f(X_i – c) + \beta^\top Z_i + \varepsilon_i

\end{equation}

For letting the covariates interact with the treatment indicator, the sort of model we want to avoid looks like this:

\begin{equation}

Y_i = \alpha + \tau D_i + f(X_i – c) + \beta^\top (Z_i \cdot D_i) + \varepsilon_i

\end{equation}

Now, let’s distinguish between two ways of practically including covariates:

- Direct inclusion: Add them directly to the outcome model alongside the treatment and running variable.

- Residualisation: First regress the outcome on the covariates, then use the residuals in the RDD.

We’ll use residualisation in our case. It’s an effective way reduce noise, produces cleaner visualisations, and protects the strategic value of the data.

The snippet below defines the outcome de-noising model and computes the residualised outcome, click_res. The idea is simple: once we strip out the variance explained by the covariates, what remains is a less noisy version of our outcome variable—at least in theory. Less noise means more accuracy.

In practice, though, the residualisation barely moved the needle this time. We can see that by checking the change in standard deviation:

SD(click_res) / SD(click) - 1 gives us about -3%, which is small practically speaking.

# denoising clicks

mod_outcome_model <- lm(click ~ l1 + organic + boosted,

data = df_listing_level)

df_listing_level$click_res <- residuals(mod_outcome_model)

# the impact on variance is limited: ~ -3%

sd(df_listing_level$click_res) / sd(df_listing_level$click) - 1Even though the denoising didn’t have much effect, we’re still in a good spot. The original outcome variable already has low conditional variance, and patterns around the cutoff are visible to the naked eye, as we can see below.

We move on to a few other modelling decisions that generally have a bigger impact: choosing between parametric and non-parametric RDD, the polynomial degree and the bandwidth parameter (h).

Modelling choices in RDD

Parametric vs non-parametric RDD

You might wonder why we even have to choose between parametric and non-parametric RDD. The answer lies in how each approach trades off bias and variance in estimating the treatment effect.

Choosing parametric RDD is essentially choosing to reduce variance. It assumes a specific functional form for the relationship between the outcome and the running variable, \(\mathbb{E}[Y \mid X]\), and fits that model across the entire dataset. The treatment effect is captured as a discrete jump in an otherwise continuous function. The typical form looks like this:

$$Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 D + \beta_2 X + \beta_3 D \cdot X + \varepsilon$$

Non-parametric RDD, on the other hand, is about reducing bias. It avoids strong assumptions about the global relationship between Y and X and instead estimates the outcome function separately on either side of the cutoff. This flexibility allows the model to more accurately capture what’s happening right around the threshold. The non-parametric estimator is:

\(\tau = \lim_{x \downarrow c} \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x] – \lim_{x \uparrow c} \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x]\)

So, which should you choose? Honestly, it can feel arbitrary. And that’s okay. This is the first in a series of judgment calls that practitioners often call the fun part of RDD. It’s where modelling becomes as much an art as it is a science.

I’ll walk through how I approach that choice. But first, let’s look at two key tuning parameters (especially for non-parametric RDD) that will guide our final decision: the polynomial degree and the bandwidth, h.

Polynomial degree

The relationship between outcome and the running variable can take many forms, and capturing its true shape is crucial for estimating the causal effect accurately. If you’re lucky, everything is linear and there is no need to think of polynomials — If you’re a realist, then you probably want to learn how they can serve you in the process.

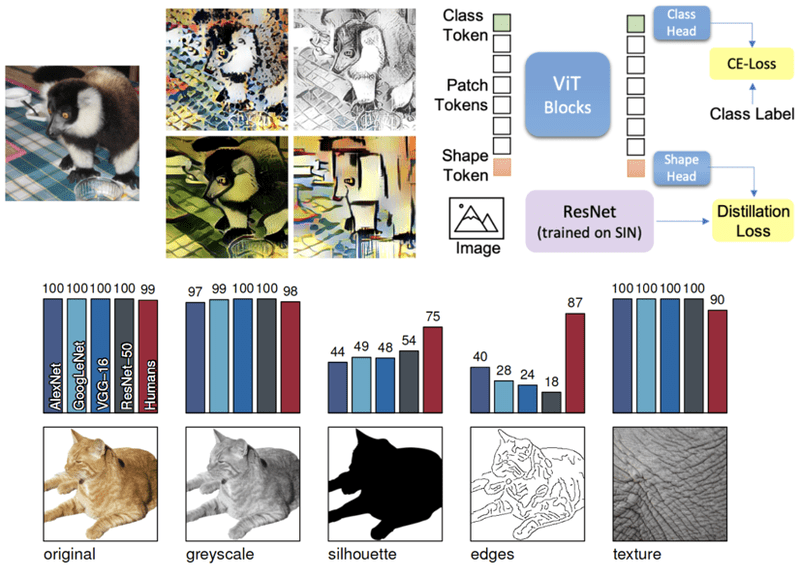

In selecting the right polynomial degree, the goal is to reduce bias, without inflating the variance of the estimator. So we want to allow for flexibility, but we don’t want to do it more than necessary. Take the examples in the image below: with an outcome of low enough variance, the linear form naturally invites the eyes to estimate the outcome at the cutoff. But the estimate becomes biased with only a slightly more complex form, if we enforce a linear shape in the model. Insisting on a linear form in such a complex case is like fitting your feet into a glove: It kind of works, but it’s very ugly.

Instead, we give the model more degrees of freedom with a higher-degree polynomial, and estimate the expected

The bandwidth parameter: h

Working with polynomials in the way that’s described above does not come free of worries. Two things are required and pose a challenge at the same time:

- we need to get the modelling right for entire range, and;

- the entire range should be relevant for the task at hand, which is estimating \(\tau = \lim_{x \downarrow c} \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x] – \lim_{x \uparrow c} \mathbb{E}[Y \mid X = x]\)

Only then we reduce bias as intended; If one of these two is not the case, we risk adding more of it.

The thing is that modelling the entire range properly is more difficult than modelling a smaller range, specially if the form is complex. So, it’s easier to make mistakes. Moreover, the entire range is almost certain not to be relevant to estimate the causal effect — the “local” in LATE gives it away. How do we work around this?

Enter the bandwidth parameter, h. The bandwidth parameters aids the model in leveraging data that is closer to the cutoff, dropping the global data idea, and bringing it back to the local scope RDD estimates the effect for. It does so by weighting the data by some function \(\mathbb{w}(X)\) so that more weight is given to entries near the cutoff, and less to the entries further away.

For example, with h = 10, the model considers the range of total length 20; 10 on each side of the cutoff.

The effective weight depends on the function, \(\mathbb{w}\). A bandwidth function that has a hard-boundary behaviour is called a square, or uniform, kernel. Think of it as a function that gives weights 1 when the data is within bandwidth, and 0 otherwise. The gaussian and triangular kernels are two other frequently used kernels by practitioners. The key difference is that these behave less abruptly in weighting of the entries, compared to the square kernel. The image below visualises the behaviour of the three kernels functions.

Everything put together: non- vs. parametric RDD, polynomial degree and bandwidth

To me, choosing the final model boils down to the question: what is the simplest model that does the good job? Indeed — the principle of Occam’s razor never goes out of fashion. In practise, this means:

- Non- vs. Parametric: is the functional form simple on both sides of the cutoff? Then a single fit, pooling data from both sides will do. Otherwise, nonparametric RDD adds the flexibility that is needed to embrace two different dynamics on either side of the cutoff.

- Polynomial degree: when the function is complex, I opt-in for higher degrees to follow the trend better flexibly.

- Bandwidth: if just picked a high polynomial degree, then I will let h be larger too. Otherwise, lower values for h often go well with lower degrees of polynomials in my experience*, **.

* This brings us to the generally accepted recommendation in the literature: keep the polynomial degree lower than 3. In most use cases 2 works well enough. Just make sure you pick mindfully.

** Also, note that h fits especially well in the non-parametric mentality; I see these two choices as co-dependent.

Back to the listing position scenario. This is the final model to me:

# modelling the residuals of the outcome (de-noised)

mod_rdd <- lm(click_res ~ D + ad_position_idx,

weight = triangular_kernel(x = ad_position_idx, c = 0, h = 10), # this is h

data = df_listing_level)Interpreting RDD results

Let’s look at the model output. The image below shows us the model summary. If you’re familiar with that, it all will come down to interpreting the parameters.

The first thing to look at is that treated listings have ~1% point higher probability of being clicked, than untreated listings. To put that in perspective, that’s a +20% change if the click rate of the control is 5%, and ~ +1% increase if the control is 80%. When it comes to practical significance of this causal effect, these two uplifts are day and night. I’ll leave this open-ended with a few questions to take home: when would you and your team label this impact as an opportunity to jump on? What other data/answers do we need to declare this track worthy of following?

The remainder of the parameters don’t really add much to the interpretation of the causal effect. But let’s go over them quickly, nonetheless. The second estimate (x) is that of the slope below cutoff slope; the third one (D x \(\mathbb(x)\)) is the additional [negative] points added to the previous slope to reflect the slope above the cutoff; Finally, the intercept is the average for the units right below the cutoff. Because our outcome variable is residualised, the value -0.012 is the demeaned outcome; it no longer is on the scale of the original outcome.

Different choices, different models

I’ve put this image together to show a collection of other possible models, had we made different choices in bandwidth, polynomial degree, and parametric-versus-not. Although hardly any of these models would have put the decision maker on a totally wrong path in this particular dataset, each model comes with its bias and variance properties. This does colour our confidence of the estimate.

Placebo testing

In any causal inference method, the identification assumption is everything. One thing is off, and the entire analysis crumbles. We can pretend everything is alright, or we put our methods to the test ourselves (believe me, it’s better when you break your own analysis before it goes out there)

Placebo testing is one way to corroborate the results. Placebo testing checks the validity of results by using a setup identical to the real one, minus the actual treatment. If we still see an effect, it signals a flawed design — continuity can’t be assumed, and causal effects can’t be identified.

Good for us, we have a placebo group. The 30-listing page cut only exists on the desktop version of the platform. On mobile, infinite scroll makes it one long page; no pagination, no page jump. So the effect of “going to the next page” shouldn’t appear, and it doesn’t.

I don’t think we need to do much inference. The graph below already tells us the entire story: without pages, going from the 30th position to the 31st is not different from going from any other position to the next. More importantly, the function is smooth at the cutoff. This finding adds a great deal of credibility to our analysis by showcasing that continuity holds in this placebo group.

The placebo test is one of the strongest checks in an RDD. It tests the continuity assumption almost directly, by treating the placebo group as a stand-in for the counterfactual.

Of course, this relies on a new assumption: that the placebo group is valid; that it is a sufficiently good counterfactual. So the test is powerful only if that assumption is more credible than assuming continuity without evidence.

Which means that we need to be open to the possibility that there is no proper placebo group. How do we stress-test our design then?

No-manipulation and the density continuity test

Quick recap. There are two related sources of confounding and hence to violating the continuity assumption:

- direct confounding from a third variable at the cutoff, and

- manipulation of the running variable.

The first can’t be tested directly (except with a placebo test). The second can.

If units can shift their running variable, they self-select into treatment. The comparison stops being fair: we’re now comparing manipulators to those who couldn’t or didn’t. That self-selection becomes a confounder, if it also affects the outcome.

For instance, students who did not make the cut for a scholarship, but go on to effectively smooth-talk their institution into letting them pass with a higher score. That silver tongue can also help them getting better salaries, and act as confounder when we study the effect of scholarships on future income.

So, what are the signs that we’re in such scenario? An unexpectedly high number of units just above the cutoff, and a dip just below (or vice versa). We can see this as another continuity question, but this time in terms of the density of the samples.

While we can’t test the continuity of the potential outcomes directly, we can test the continuity of the density of the running variable at the cutoff. The McCrary test is the standard tool for this, exactly testing:

\(H_0: \lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) = \lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) \quad \text{(No manipulation)}\)

\(H_A: \lim_{x \to c^-} f(x) \neq \lim_{x \to c^+} f(x) \quad \text{(Manipulation)}\)

where \(f(x)\) is the density function of the running variable. If \(f(x)\) jumps at x = c, it suggests that units have sorted themselves just above or below the cutoff — violating the assumption that the running variable was not manipulable at that margin.

The internals of this test is something for a different post, because luckily we can rely rdrobust::rddensity to run this test, off-the-shelf.

require(rddensity)

density_check_obj <- rddensity(X = df_listing_level$ad_position_idx,

c = 0)

summary(density_check_obj)

# for the plot below

rdplotdensity(density_check_obj, X = df_listing_level$ad_position_idx)

The test shows marginal evidence of a discontinuity in the density of the running variable (T = 1.77, p = 0.077). Binomial counts are unbalanced across the cutoff, suggesting fewer observations just below the threshold.

Usually, this is a red flag as it may pose a thread to the continuity assumption. This time however, we know that continuity actually holds (see placebo test).

Moreover, ranking is done by the algorithm: sellers have no means to manipulate the rank of their listings at all. That’s something we know by design.

Hence, a more plausible explanation is that the discontinuity in the density is driven by platform-side impression logging (not ranking), or my own filtering in the SQL query (which is elaborate, and missing values on the filter variables are not uncommon).

Inference

The results will do this time around. But Calonico, Cattaneo, and Titiunik (2014) highlight a few issues with OLS RDD estimates like ours. Specifically, about 1) the bias in estimating the expected outcome at the cutoff, that no longer is really at the cutoff when we take samples further away from it, and 2) the bandwidth-induced uncertainty that is left out of the model (as h is treated as a hyperparameter, not a model parameter).

Their methods are implemented in rdrobust, an R and Stata package. I recommend using that software in analyses that are about driving real-life decisions.

Analysis recap

We looked at how a listing’s spot in the search results affects how often it gets clicked. By focusing on the cutoff between the first and second page, we found a clear (though modest) causal effect: listings at the top of page two got more clicks than those stuck at the bottom of page one. A placebo test backed this up—on mobile, where there’s infinite scroll and no real “pages,” the effect disappears. That gives us more confidence in the result. Bottom line: where a listing shows up matters, and prioritising top positions could boost engagement and create new commercial possibilities.

But before we run with it, a couple of important caveats.

First, our result is local—it only tells us what happens near the page-two cutoff. We don’t know if the same effect holds at the top of page one, which probably signals even more value to users. So this might be a lower-bound estimate.

Second, volume matters. The first page gets a lot more eyeballs. So even if a top slot on page two gets more clicks per view, a lower spot on page one might still win overall.

Conclusion

Regression Discontinuity Design is not your everyday causal inference method — it’s a nuanced approach best saved for when the stars align, and randomisation isn’t doable. Make sure that you have a good grip on the design, and be thorough about the core assumptions: try to break them, and then try harder. When you have what you need, it’s an incredibly satisfying design. I hope this reading serves you well the next time you get an opportunity to apply this method.

It’s great seeing that you got this far into this post. If you want to read more, it’s possible; just not here. So, I compiled a small list of resources for you:

- Causal Inference Mixtape: for an extensive read on RDD and more

- Causal Inference: A Statistical Learning Approach: formal and technically to the point

- and of course our trusty Wikipedia (actually great to get started)

Also check out the reference section below for some deep-reads.

Happy to connect on LinkedIn, where I discuss more topics like the one here. Also, feel free to bookmark my personal website that is much cosier than here.

All images in this post are my own. The dataset that I used is real, and it is not publicly available. Moreover, the values extracted from it are anonymised; modified or omitted, to avoid revealing strategic insights about the company.

References

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., Farrell, M. H., & Titiunik, R. (2018). Regression Discontinuity Designs Using Covariates. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1809.03904v1

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M. D., & Titiunik, R. (2014). Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica, 82(6), 2295–2326. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11757

The post Regression Discontinuity Design: How It Works and When to Use It appeared first on Towards Data Science.

![Apple Shares Official Trailer for 'Echo Valley' Starring Julianne Moore, Sydney Sweeney, Domhnall Gleeson [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97250/97250/97250-640.jpg)

![Netflix Unveils Redesigned TV Interface With Smarter Recommendations [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97249/97249/97249-640.jpg)

_Wavebreakmedia_Ltd_IFE-240611_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Alexey_Kotelnikov_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![[The AI Show Episode 146]: Rise of “AI-First” Companies, AI Job Disruption, GPT-4o Update Gets Rolled Back, How Big Consulting Firms Use AI, and Meta AI App](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20146%20cover.png)

-Pokemon-GO---Official-Gigantamax-Pokemon-Trailer-00-02-12.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.jpg?#)