The Architecture of Mathematics – And How Developers Can Use it in Code

"To understand is to perceive patterns." - Isaiah Berlin Math is not just numbers. It is the science of finding complex patterns that shape our world. This means that to truly understand it, we need to see beyond numbers, formulas, and theorems and ...

"To understand is to perceive patterns." - Isaiah Berlin

Math is not just numbers. It is the science of finding complex patterns that shape our world. This means that to truly understand it, we need to see beyond numbers, formulas, and theorems and understand its structures.

The main goal of this article is to show how math is just like a growing tree of ideas. I want to show that math is a living system of logic, not just formulas to memorize. With analogies, history, and code examples, I want to help you understand math more deeply and how you can apply it to programming.

I’ve also included some code examples here to help you connect theory and practice. I show them to demonstrate how math ideas are applied to real problems. Whether you are new to more advanced math or are more experienced, these code examples will help you understand how to apply math in programming.

This link across theory and application reflects my own studies. I am a finalist in an undergraduate degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering at NOVA FCT, one of the best engineering faculties in Portugal.

My engineering degree is one with more math and physics. This is because it’s key to get a solid grasp of math to understand electronics, telecommunications, control theory, and other areas of engineering.

Here’s a brief overview of some of the math and physics subjects I’ve learned:

Partial Differential Equations (PDEs): These equations model real-world phenomena, from heat diffusion to the economy of a country.

Harmonic Analysis (Fourier & Laplace): Integral transforms like the Fourier and Laplace transform allow us to understand problems in new domains.

Complex Analysis: Extending calculus into the complex plane gives rise to powerful tools used in physics and engineering.

Numerical Analysis: When analytical solutions are impossible or inefficient, numerical methods provide computer-based approximations. This is crucial for real-world applications.

Control and Signal Theory: These areas show us how to design stable systems like rockets, trains, and robots.

Physics: Courses in Classical Mechanics and Electromagnetism helped bridge theoretical math to physical laws

During my years of study, besides technical skills, I’ve developed a deeper understanding of how the world works and the structure of the field of mathematics. And I’ve started to find patterns in how math is a framework of interconnected logic.

In this article, we’ll explore:

Simple Analogy: The Tree of Mathematics

Imagine math as a vast tree growing forever.

The roots of the tree are the foundations of mathematics: logic and set theory. From this foundation emerge the main basic fields of math: arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and analysis.

As the tree divides further and further into more branches, new, more complex subfields start to appear, like topology, abstract algebra, and complex analysis. Sometimes the branches are connected to each other.

And remember: this tree is always growing in many directions. From branches creating new branches to branches connecting to other branches. Little by little, it grows.

Throughout history, there have been times that, due to some big scientific discoveries, parts of the math tree started to grow very fast. Other times, decades and even centuries passed without many new branches. This is the case for imaginary numbers, for example.

And you might wonder: How many more branches and connections between them will keep appearing?

The Structure and History of Mathematics

The first mathematical ideas appeared independently across ancient civilizations. For example:

India’s invention of zero

Islamic algebraic advances

Greek geometric rigor

Over time, many different great mathematicians created and shared them by writing and giving lectures.

Eventually, these new ideas were shared widely with new generations and these new generations created new math based on old math.

This is is how new branches are continuously born from previous branches of the tree of mathematics.

And this is why Isaac Newton wrote, in a letter to Robert Hooke in 1675:

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants

He meant that by working from previous knowledge, he was able to create and (re)discover new ideas.

Yet, the real power of math lies in practicing it over and over and understanding it more and more deeply. As one of my professors once explained:

More important than knowing the theorems is knowing the ideas behind them and the history of how they were created.

Very often, to solve problems, it is necessary to think in terms of first principles and build from there. Math teaches exactly that. In this way, math is not just an academic subject. It is a language spoken by scientists and engineers around the globe.

By having it well preserved and shared, it is still possible to create new math from previous ideas. And it’s possible for the big tree to continue growing based on previous branches or nodes.

An Tree example: Foundations of Relativity by Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein created the general and special theories of relativity. These have big consequences nowadays:

GPS and Global Communication

Advancements in Satellite Telecommunications

Space Exploration and Satellite Launches

But this was only possible through the unification of geometry with calculus, called differential geometry. The evolution of differential geometry happened over the centuries, thanks to many great mathematicians. Below are some of them, but this is not a complete list:

Euclid (circa 300 BCE): Contributed to geometry, laying the groundwork for later mathematical systems

Archimedes (circa 287–212 BCE): Pioneered the understanding of volume, surface area, and the principles of mechanics

René Descartes (1596–1650): Developed Cartesian coordinates and analytical geometry

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) & Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716): Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation, alongside Leibniz’s development of calculus, formed the basis of classical mechanics that Einstein sought to extend and modify in his theory of relativity.

Leonhard Euler (1707–1783): Contributed to the development of differential equations, which are essential in the mathematical foundations of physics.

Gaspard Monge (1746–1818): The father of differential geometry and pioneer in descriptive geometry

Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855): Made groundbreaking advances in geometry, including the concept of curved surfaces.

Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866): Introduced Riemannian geometry, a branch of differential geometry.

Once again, as Isaac Newton wrote, in a letter to Robert Hooke in 1675:

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

Albert Einstein saw what no one else in his time saw, thanks to these great math giants and countless others.

The Biggest Paradox of Math, Discovered by Kurt Gödel

The biggest paradox in math, in my opinion, is what Kurt Gödel discovered. His early 20th century research revealed a limitation within this cycle.

This paradox – that is, his incompleteness theorems – shows that in any consistent formal system capable of expressing simple arithmetic, there will always be true mathematical statements that cannot be proven within the system itself.

This means that in ALL systems, there are limits to what you can actually prove as to what is true and false. For for mathematicians, this means that the tree will never be completed. There are truths that are beyond formal truths, and yet we still assume that they are true (albeit unproven).

This way, it proves that no matter how many mathematicians work in the field or how much AI is used to find new mathematics, there will always exist limitations. Some things are impossible to prove that are true, and we just know that they are due to approximation estimations and other non logical exact methods.

What About Applied Math and Engineering?

Applied math and engineering involves interpreting the same pure math ideas in real-world scenarios. Actually, in many cases, it is the combination of many math ideas. Let’s consider some examples:

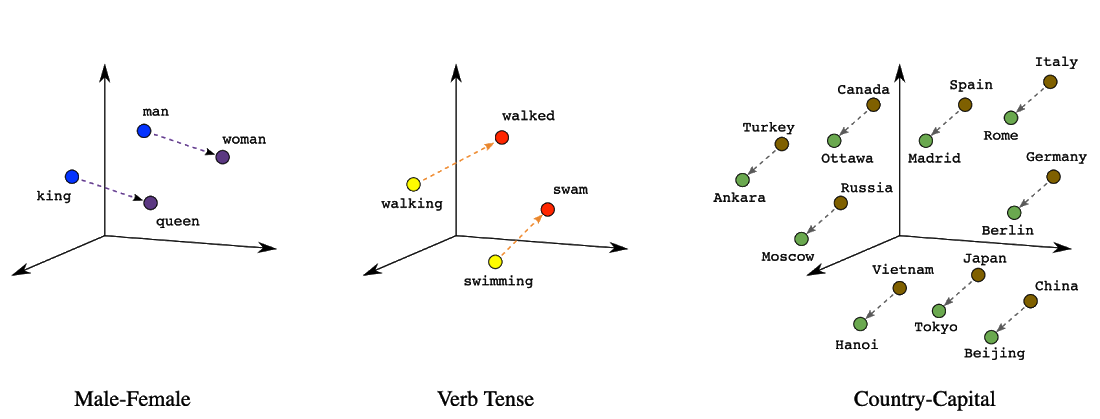

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a widely used tool in data science. Yet, it is a mixture of linear algebra (in PCA, eigenvalues) with optimization (order eigenvalues that represent more data with less data) in order to make datasets shorter.

In machine learning, logistic regression is a mixture of calculus with statistics and probability.

In harmonic analysis, Laplace, Fourier, and Z-transforms are a way to see the same thing in a new domain to get new insights. In this case, integrals are used to make this mapping.

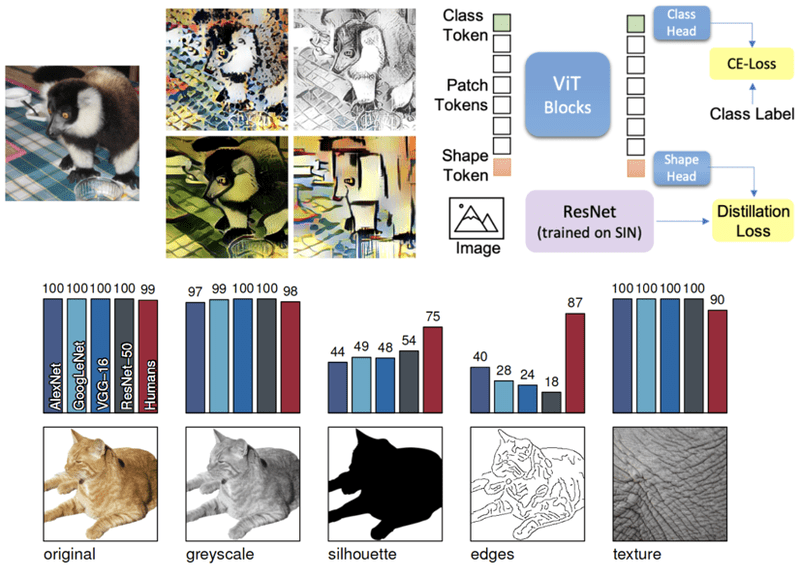

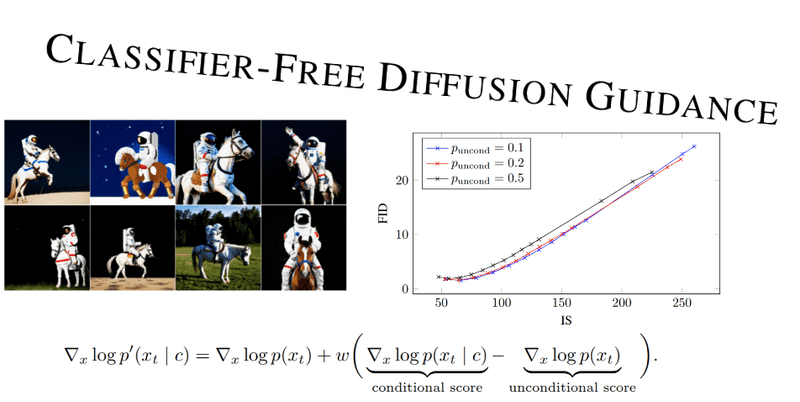

In deep learning, neural networks are just many matrices multiplying and updating themselves that adapt to model a dataset representing a system. This optimization of matrix values happens with activation functions, a gradient descent-based optimization method (tells how much values need to change), and backpropagation (applies those alterations to all matrix values).

I have actually written an article where I teach why activation functions are important if you want to check it out.

But the best example of this fusion of math with engineering is in control theory.

Control theory is the study of the architecture of systems. From trains to cars to airplanes, everything is based on control theory. It is everywhere in nearly all modern electronic devices. In electric circuits, control theory is also used heavily to guarantee circuit stability in the face of electric disturbances.

So as you can probably start to see, many of the tools we now have are just a mixture of many pure math ideas. Just many combinations and recipes of pure math ideas. In essence, applied math is the application of pure math as “ingredients“ in "recipes" to solve problems.

So, we’ve explored the structure and evolution of mathematics. Yet, it is important to see how these ideas can be applied in real life. Pure math makes the framework, and applied math applies that framework to solve problems. To understand this, we’ll examine two code examples that show how you can use math ideas as programming tools.

Code Examples – Analytical and Numerical Approaches

These code examples demonstrate a couple ways you can use Python to solve math equations.

In the first code example, we’ll solve the problem in the same way that kids in school solve math exercises: essentially, by hand with a pencil. Moving variables from left to right to find their values. In the second example, we’ll solve the problem using numerical analysis.

Example 1: Solve a Problem Analytically

When we solve math problems analytically, like we did in school, we are manipulating symbols to get exact values. Often there symbols are x, y and z. In Python, we can do this using the SymPy library:

from sympy import symbols, Eq, solve

x, y = symbols('x y')

eq1 = Eq(2*x + 3*y, 6)

eq2 = Eq(-x + y, 1)

solution = solve((eq1, eq2), (x, y))

print(solution)

Essentially, we are finding x and y based on this equation:

$$\begin{align*} 2x + 3y &= 6 \\ -x + y &= 1 \end{align*}$$

Which gives us the following result:

{x: 3/5, y: 8/5}

Or:

x= 0.6

y = 1.6

When we say that we’re solving this analytically, it means that we’re finding an exact mathematical solution using formulas or equations.

But many times, problems are harder and can be solved by adding symbols to the right or left of the equation.

Sometimes, there can be so many symbols and transformed versions of them, with things like derivatives and integrals, that it can become very hard to manage and takes a lot of time.

For this reason, there is an area of mathematics devoted to finding approximations of already created mathematical formulas called numerical analysis. It makes it faster to solve these problems. And this is the method we will explore next.

Example 2: Solve Numerically (Approximation)

We’ll now use SciPy to solve the same system with numerical methods:

import numpy as np

from scipy.linalg import solve

A = np.array([[3, 2, -1, 4, 5],

[1, 1, 3, 2, -2],

[4, -1, 2, 1, 0],

[5, 3, -2, 1, 1],

[2, -3, 1, 3, 4]])

b = np.array([12, 5, 7, 9, 10])

solution = solve(A, b)

print(solution)

In this code example, this line of code:

solution = solve(A, b)

Uses the solve method from the SciPy Python library:

from scipy.linalg import solve

It’s a method that helps you find the values of x in an equation A⋅x=b, where a is a square grid of numbers and b is a list of numbers. Which gives us the following:

[ 1.35022026 -0.79955947 -1.17180617 3.14317181 -0.83920705]

Now imagine, in this simple case, that a matrix like A could represent the traffic flow between cities or intersections, and b could represent the traffic entering or leaving each city.

By solving the system, it could help us determine the distribution of traffic between cities to meet desired traffic conditions.

Of course, these types of problems are far more complex in real life. But to understand and solve the big problems, you need to first understand the smaller problems.

And by the way, a system of equations is the same thing as a matrix. We just represent systems of equations as matrices to make the findings of properties and clarity easier to understand.

The thing is that by using matrices, it is easier to make calculations and to perform linear algebra math to check for characteristics of the matrix and understand it better.

In essence, a matrix represents a system of equations. Also, systems of equations can represent real life phenomena like the economy of a country or the weather.

If you want to know more, I wrote an entire article on numerical analysis that you can check out.

The Impact of a Grand Unified Theory of Mathematics

Despite the biggest paradox in mathematics, what would happen with a Grand Unified Theory of Mathematics?

Remember that such a theory tells us that there are things that are true that are impossible to formally prove, and we need to just accept it. But even with this assumption, it is still possible to unify all math.

This is what the Langland's program is trying to solve. A kind of attempt to interconnect the largest parts of the big tree of math to uncover new patterns in math.

With a Grand Unified Theory of Mathematics, we would be able to understand how every branch of the tree connects with the others and all the relationships between them.

What is the value of this big unification for society?

By studying history, we can find patterns. The unification of various fields has created many massive impacts on society, such as:

In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell united the fields of electricity and magnetism with his famous Maxwell equations. This allowed the creation of radios and electric grids around the globe. In turn, it served as a foundation for all technological progress in the 20th and 21th century.

In the 20th century, the unification of algebra with logic led to the rise of digital systems. In turn, digital systems gave the rise of processors and the evolution of computers to the modern laptop.

Also in the 20th century, the unification of probability and communication led to information theory. This became the foundation for the internet. This unification was carried out by a great mathematician called Clause Shannon.

In the end, a Grand Unified Theory of Mathematics could be one of the biggest achievements in modern society.

It could lead to new discoveries in physics, such as in string theory or quantum gravity, where deep mathematical structures are needed to create new physics. In AI, it could help unify all machine learning models in a common architecture. This would help accelerate the development of new AI models. It could also open the door to new cryptographic methods and material science advances, revealing, with math, the deep patterns still not found in these fields.

Just as uniting electricity and magnetism led to modern technology, a unified math framework would lead to a wave of innovation.

A Final Lesson From History

From Greek geometry to AI, math has grown like a tree over centuries. By understanding its structure, it is possible to see its role in finding the patterns of our universe. I hope I was able to make you see math in this way.

In addition, we can conclude that the unification of scientific fields makes the foundations for the creation of new innovations to help society go forward. Many profound societal transformations only came to be thanks to abstract math ideas. When these are shared and refined, they become the hidden architecture of progress in society. Innovation begins when disconnected ideas are united, well-linked, and widely shared.

Find the full code here.

![Jony Ive and OpenAI Working on AI Device With No Screen [Kuo]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97401/97401/97401-640.jpg)

![Anthropic Unveils Claude 4 Models That Could Power Apple Xcode AI Assistant [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97407/97407/97407-640.jpg)

![Apple Accelerates Smart Glasses for 2026, Cancels Watch With Camera [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97408/97408/97408-640.jpg)

-xl.jpg)

.webp?#)

_David_Hall_-Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

_Andriy_Popov_Alamy_Stock_Photo.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![[The AI Show Episode 148]: Microsoft’s Quiet AI Layoffs, US Copyright Office’s Bombshell AI Guidance, 2025 State of Marketing AI Report, and OpenAI Codex](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20148%20cover%20%281%29.png)

![Laid off but not afraid with X-senior Microsoft Dev MacKevin Fey [Podcast #173]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1747965474270/ae29dc33-4231-47b2-afd1-689b3785fb79.png?#)

-1-52-screenshot.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)