Thousands of private camera feeds found online. Make sure yours isn’t one of them

What happens in the privacy of your own home stays there. Or does it?

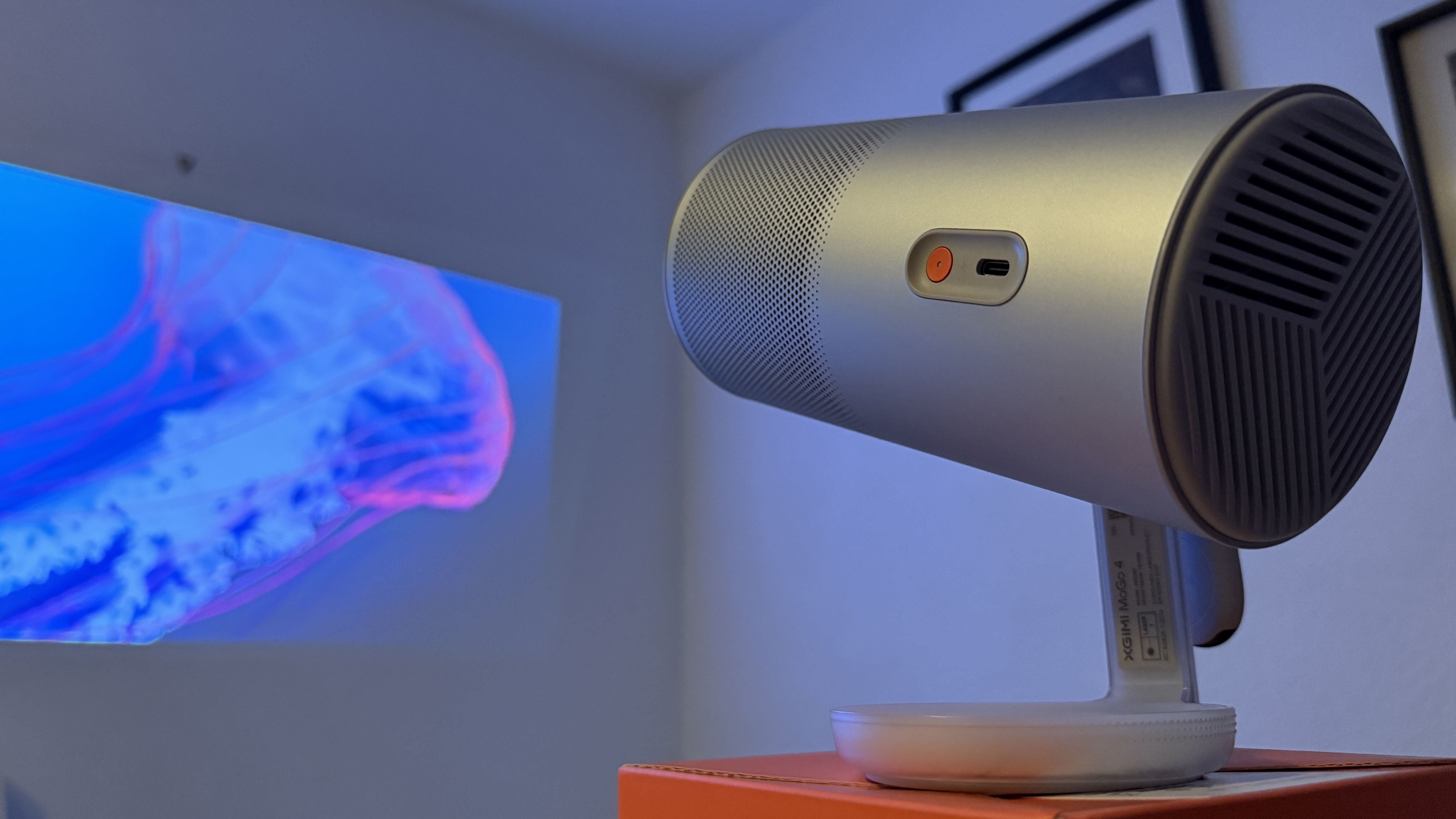

If you have internet-connected cameras in or around your home, be sure to check their settings. Researchers just discovered 40,000 of them serving up images of homes and businesses to the internet.

Bitsight’s TRACE research team revealed the issue in a report released this month. The cameras were providing the images without any kind of password or authentication, it said. While some of them were connected to businesses, showing images of offices, retail stores, and factories, many were likely connected in private residences.

Many cameras contain their own web servers that people can access remotely using a browser or app so that they can monitor their premises while away. These are often completely exposed to the internet, according to the report. That means anyone could access the video feed by typing in the right IP address.

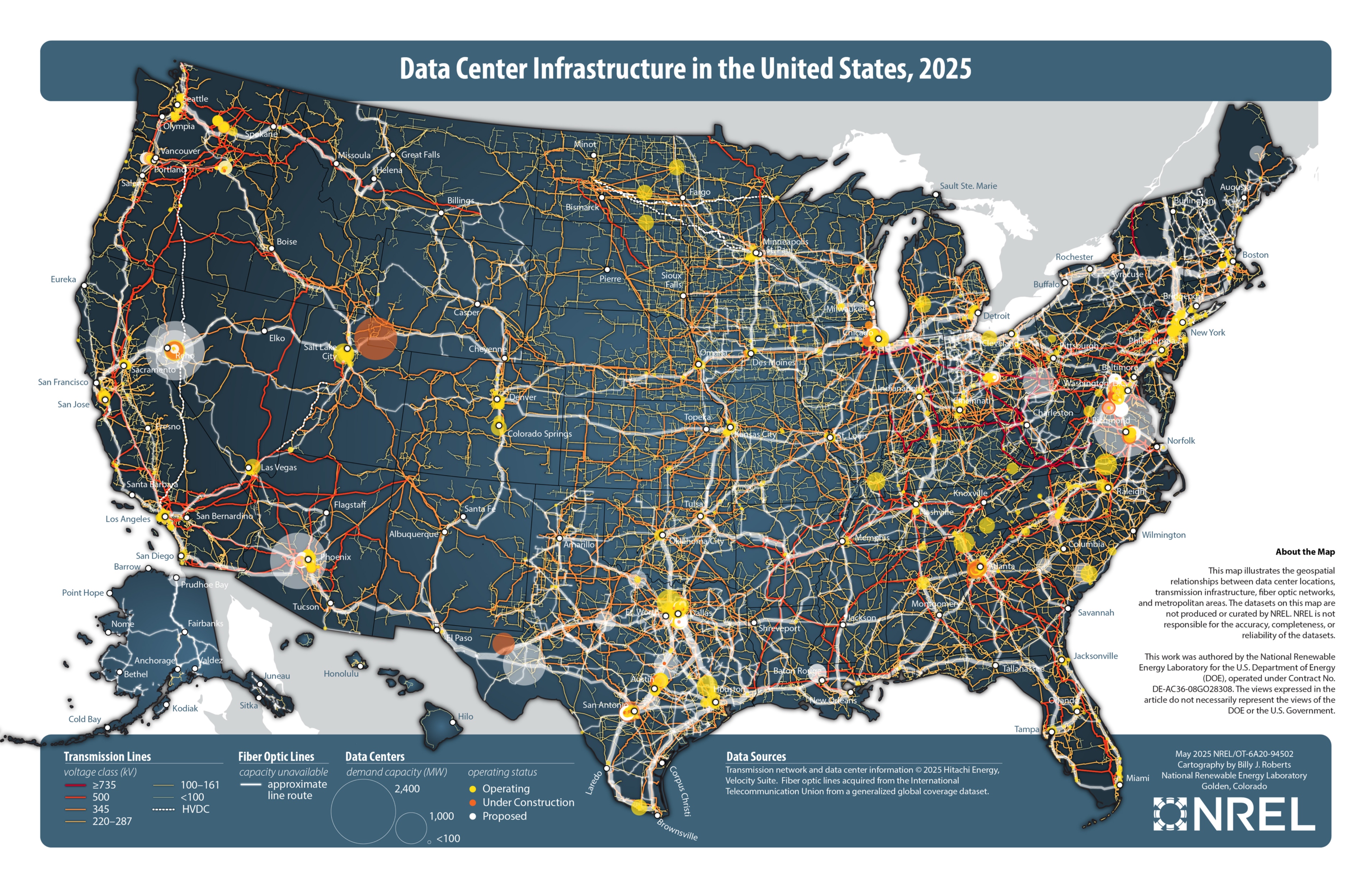

The highest number of exposed cameras by far was in the US, at around 14,000. Breaking down the states there showed the highest concentrations in California and Texas.

Japan, the second highest country, had just half that, at 7,000. After that came Austria, Czechia, South Korea, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Taiwan.

The big threat for such users is privacy. People put these cameras everywhere, including extra-private spaces in their homes like kids’ and adults’ bedrooms. Attackers might spy on people or even set them up for extortion if the images are compromising.

Aside from the obvious privacy implications, there are other security worries, the report said. Cameras could be used to gather surveillance data by someone planning a physical intrusion, it pointed out.

But access to admin interfaces is just one threat; getting SSH access (which allows someone to log into the device via a terminal and control it as they would a regular computer) could give an attacker total control over the camera’s hardware and software if they’re able to exploit vulnerabilities left there by the manufacturer.

If this happens, a camera (which is, after all, just a computer with a lens) could become a jumping-off point for the attacker to compromise other computers on the network. Or it could be joined to a botnet to do the attacker’s bidding.

Botnets made of up connected devices are common. One of the most famous such botnets, Mirai, co-opted cameras and other internet-connected systems to launch denial of service attacks, in which thousands of devices would try to connect with a target, flooding it with traffic and rendering it inoperable.

Bitsight’s report also cites one case where attackers used vulnerabilities in a camera to install ransomware on it.

A long history of camera compromise

Internet-enabled camera issues are nothing new. Finding exposed feeds, whether via Bitsight’s own scanning engine or via publicly accessible ones like Shodan.io, is like shooting fish in a barrel. Indeed, Bitsight did something similar in 2023. In the past, we’ve seen sites like Insecam (now offline), which streamed images from 40,000 unsecured video cameras around the world. Some of those cameras were doubtless there for public consumption, just as many were not.

Finding unsecured feeds is so easy because people tend to just plug these things in and turn them on, much as you might use a portable air conditioner. Vendors should force some basic cybersecurity hygiene, but they don’t, because they don’t want to introduce any costly friction. Regulation for connected smart devices like IP cameras has emerged in the US and the UK, but enforcement is another issue.

Some might advise you to only choose a respectable brand of IP camera, but you can’t always trust big-name vendors who claim to act responsibly. Last year, Amazon settled with the Federal Trade Commission, paying $5.6m over charges that its employees and contractors spied on users of its Ring cameras.

Ring allowed everyone working for it to see any customer’s feeds, the FTC said, which led to some employees repeatedly accessing feeds of young women in sensitive areas of the home. Ring also failed to protect its cameras adequately against intruders that compromised them, the FTC said. That led to intruders taking control of the cameras. They would use camera microphones to hurl racial slurs at children, and swear at women lying in bed, the complaint alleged.

Other vendor missteps have included Wyze accidentally showing customers each others’ video feeds, and Eufy sending camera images to the cloud when it said it wouldn’t.

How to protect your internet-enabled camera

We can’t think of a worse privacy scenario than having someone snoop on you and your loved ones in what is supposed to be your safest space. Letting any connected device into your home is always risky, especially when it has video capabilities. Here is some advice to minimize that risk:

- Use unique credentials. Make sure that you set unique logins and passwords for your cameras so that people can’t just stroll in and view them. That means taking some time to configure the camera through its admin interface and making sure to change the default password.

- Restrict IP camera use to non-sensitive places as much as possible. While some Ring customers apparently needed cameras in the bathroom and bedroom, we urge you to think twice.

- Research the camera for vulnerabilities. Check to see whether the brand you’re considering has had any security issues in the past, and how quickly the issues have been fixed.

- Try accessing your camera insecurely. Try accessing your camera remotely without using your login credentials. If you can, then so can everyone else.

- Patch regularly. Find out how to update your device with the latest security patches and check for updates regularly, or preferably set it to update automatically if you can.

We don’t just report on threats—we remove them

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Keep threats off your devices by downloading Malwarebytes today.

![Apple Releases New Beta Firmware for AirPods Pro 2 and AirPods 4 [8A293c]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97704/97704/97704-640.jpg)

![Samsung teasing Galaxy Buds ‘Core’ ahead of launch later this week [Gallery]](https://i0.wp.com/9to5google.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/10/samsung-galaxy-buds-fe-5.jpg?resize=1200%2C628&quality=82&strip=all&ssl=1)

_ArtemisDiana_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![[The AI Show Episode 155]: The New Jobs AI Will Create, Amazon CEO: AI Will Cut Jobs, Your Brain on ChatGPT, Possible OpenAI-Microsoft Breakup & Veo 3 IP Issues](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20155%20cover.png)

.png?width=1920&height=1920&fit=bounds&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp#)