Exploring Chinese Philosophical Concepts and Jalal Khawaldeh’s Waste of Thinking in “Collisional Thinking Theory (CTT)”

In the realm of philosophical and cultural exploration, the concept of “Waste of Thinking” in Collisional Thinking Theory (CTT), proposed by Jalal Khawaldeh, offers a unique perspective on how discarded ideas can be reimagined as valuable resources for creativity and innovation. This notion finds intriguing parallels and contrasts when compared to traditional Chinese philosophical concepts such as “Wu Wei”, “Jing”, “Yin and Yang”, and “Cao Qi”. These Chinese ideas, deeply rooted in Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, emphasize balance, simplicity, and efficiency, much like the Japanese concept of “Muda”, which focuses on eliminating waste. However, when juxtaposed with “Waste of Thinking”, these Chinese concepts reveal both convergences and divergences in their approaches to thought, action, and resource utilization. At its core, “Waste of Thinking” challenges conventional notions of intellectual waste by reframing discarded or overlooked ideas as latent opportunities for innovation. It encourages individuals to revisit and integrate these ideas into new cognitive frameworks, fostering creativity through collisions of contrasting thoughts. Similarly, the Taoist principle of “Wu Wei” — often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action” — advocates for achieving harmony with nature and minimizing unnecessary effort. While “Wu Wei” emphasizes avoiding wasteful actions, “Waste of Thinking” redirects focus toward utilizing seemingly wasted mental resources. Both concepts share a common goal of optimizing processes, yet they differ in their methods: “Wu Wei” seeks balance through restraint, whereas “Waste of Thinking” seeks progress through intentional engagement with discarded ideas. Another striking comparison can be drawn with the Confucian value of “Jing”, which represents simplicity, humility, and adherence to essential principles. In Confucian thought, excess and extravagance are discouraged, aligning with the idea of reducing waste. However, “Jing” primarily addresses external behavior and societal norms, while “Waste of Thinking” delves into internal cognitive processes. The integration of these two perspectives could inspire individuals to adopt a minimalist yet innovative mindset, where simplicity in thought and action coexists with the creative reuse of neglected ideas. The dualistic philosophy of “Yin and Yang” also resonates with “Waste of Thinking”. In Taoism, “Yin” and “Yang” symbolize complementary forces that maintain cosmic balance. This duality mirrors the interplay between primary and discarded ideas in CTT, where contradictions and overlooked elements collide to produce novel insights. Just as “Yin” cannot exist without “Yang”, “Waste of Thinking” posits that discarded ideas hold untapped potential only when reintegrated with dominant thoughts. This parallel underscore the importance of embracing opposites and contradictions to achieve meaningful results. Furthermore, the Chinese concept of “Cao Qi”, which emphasizes frugality and economic use of resources, aligns closely with the practical implications of “Waste of Thinking”. Both advocate for sustainability — not merely in material terms but also in intellectual endeavors. By encouraging individuals to document, reflect upon, and revisit discarded ideas, CTT ensures that no cognitive resource is squandered. This approach echoes the Confucian ideal of living modestly and using resources wisely, creating a bridge between ancient wisdom and modern cognitive theory. Despite these similarities, there are notable differences in the philosophical underpinnings of these concepts. For instance, Chinese philosophies often prioritize harmony and equilibrium, reflecting a holistic worldview that integrates human actions with natural order. In contrast, “Waste of Thinking” leans more toward dynamic disruption, leveraging cognitive collisions to drive innovation. While Chinese traditions emphasize maintaining balance, CTT thrives on introducing controlled chaos to stimulate creativity. This divergence highlights the complementary nature of these philosophies: one fosters stability, while the other catalyzes change. Moreover, cultural and educational influences play a significant role in shaping how these concepts are applied. In societies influenced by Confucian values, structured learning environments may limit exposure to unconventional ideas, making it challenging to adopt “Waste of Thinking”. Conversely, Taoist-inspired cultures might embrace the fluidity and adaptability required for CTT. Understanding these nuances is crucial for integrating “Waste of Thinking” into diverse cultural contexts, ensuring its relevance across different societies. Ultimately, the dialogue between “Waste of Thinking” and Chinese philosophical concepts enriches our understanding of intellectual efficiency and creativity. By drawing inspiration from “Wu Wei”, “Jing”, “Yin and Yang”, and “Cao Qi”, we can refine the application of CTT, blending timeless wisdom

In the realm of philosophical and cultural exploration, the concept of “Waste of Thinking” in Collisional Thinking Theory (CTT), proposed by Jalal Khawaldeh, offers a unique perspective on how discarded ideas can be reimagined as valuable resources for creativity and innovation. This notion finds intriguing parallels and contrasts when compared to traditional Chinese philosophical concepts such as “Wu Wei”, “Jing”, “Yin and Yang”, and “Cao Qi”. These Chinese ideas, deeply rooted in Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, emphasize balance, simplicity, and efficiency, much like the Japanese concept of “Muda”, which focuses on eliminating waste. However, when juxtaposed with “Waste of Thinking”, these Chinese concepts reveal both convergences and divergences in their approaches to thought, action, and resource utilization.

At its core, “Waste of Thinking” challenges conventional notions of intellectual waste by reframing discarded or overlooked ideas as latent opportunities for innovation. It encourages individuals to revisit and integrate these ideas into new cognitive frameworks, fostering creativity through collisions of contrasting thoughts. Similarly, the Taoist principle of “Wu Wei” — often translated as “non-action” or “effortless action” — advocates for achieving harmony with nature and minimizing unnecessary effort. While “Wu Wei” emphasizes avoiding wasteful actions, “Waste of Thinking” redirects focus toward utilizing seemingly wasted mental resources. Both concepts share a common goal of optimizing processes, yet they differ in their methods: “Wu Wei” seeks balance through restraint, whereas “Waste of Thinking” seeks progress through intentional engagement with discarded ideas.

Another striking comparison can be drawn with the Confucian value of “Jing”, which represents simplicity, humility, and adherence to essential principles. In Confucian thought, excess and extravagance are discouraged, aligning with the idea of reducing waste. However, “Jing” primarily addresses external behavior and societal norms, while “Waste of Thinking” delves into internal cognitive processes. The integration of these two perspectives could inspire individuals to adopt a minimalist yet innovative mindset, where simplicity in thought and action coexists with the creative reuse of neglected ideas.

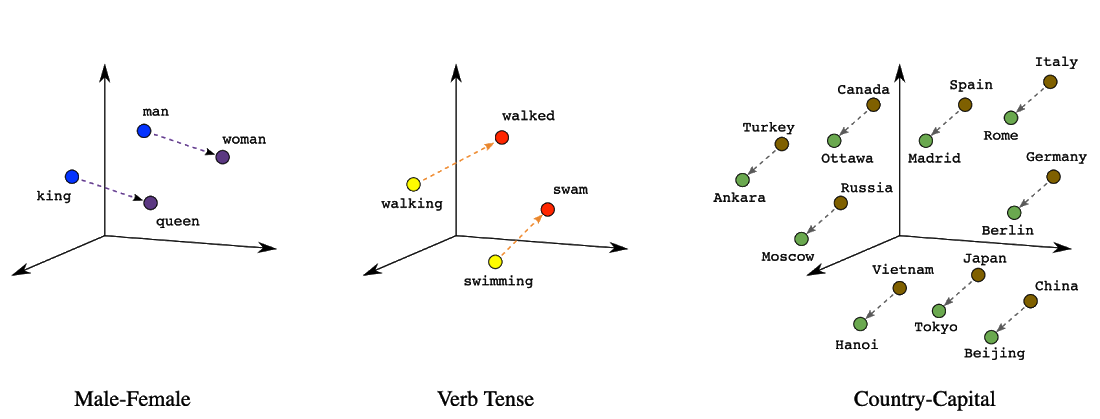

The dualistic philosophy of “Yin and Yang” also resonates with “Waste of Thinking”. In Taoism, “Yin” and “Yang” symbolize complementary forces that maintain cosmic balance. This duality mirrors the interplay between primary and discarded ideas in CTT, where contradictions and overlooked elements collide to produce novel insights. Just as “Yin” cannot exist without “Yang”, “Waste of Thinking” posits that discarded ideas hold untapped potential only when reintegrated with dominant thoughts. This parallel underscore the importance of embracing opposites and contradictions to achieve meaningful results.

Furthermore, the Chinese concept of “Cao Qi”, which emphasizes frugality and economic use of resources, aligns closely with the practical implications of “Waste of Thinking”. Both advocate for sustainability — not merely in material terms but also in intellectual endeavors. By encouraging individuals to document, reflect upon, and revisit discarded ideas, CTT ensures that no cognitive resource is squandered. This approach echoes the Confucian ideal of living modestly and using resources wisely, creating a bridge between ancient wisdom and modern cognitive theory.

Despite these similarities, there are notable differences in the philosophical underpinnings of these concepts. For instance, Chinese philosophies often prioritize harmony and equilibrium, reflecting a holistic worldview that integrates human actions with natural order. In contrast, “Waste of Thinking” leans more toward dynamic disruption, leveraging cognitive collisions to drive innovation. While Chinese traditions emphasize maintaining balance, CTT thrives on introducing controlled chaos to stimulate creativity. This divergence highlights the complementary nature of these philosophies: one fosters stability, while the other catalyzes change.

Moreover, cultural and educational influences play a significant role in shaping how these concepts are applied. In societies influenced by Confucian values, structured learning environments may limit exposure to unconventional ideas, making it challenging to adopt “Waste of Thinking”. Conversely, Taoist-inspired cultures might embrace the fluidity and adaptability required for CTT. Understanding these nuances is crucial for integrating “Waste of Thinking” into diverse cultural contexts, ensuring its relevance across different societies.

Ultimately, the dialogue between “Waste of Thinking” and Chinese philosophical concepts enriches our understanding of intellectual efficiency and creativity. By drawing inspiration from “Wu Wei”, “Jing”, “Yin and Yang”, and “Cao Qi”, we can refine the application of CTT, blending timeless wisdom with contemporary innovation. This synthesis not only enhances individual cognitive abilities but also contributes to broader societal advancements. As humanity continues to grapple with complex challenges, the fusion of these ideas offers a promising pathway toward sustainable growth and transformative thinking. Through this cross-cultural exchange, we discover that even discarded thoughts and ancient philosophies can converge to illuminate the path forward.

While the “Collisional Thinking Theory (CTT)” provides a general framework for enhancing creativity and innovation, its application across diverse societies requires careful consideration of cultural differences that may influence how individuals perceive and utilize the concept of “Waste of Thinking.” For instance, in societies that highly value tradition and social hierarchy, encouraging individuals to revisit discarded or overlooked ideas might face resistance, as such ideas are often dismissed as irrelevant or even counter-cultural. In these contexts, it is essential to present the theory in a way that aligns with traditional values, emphasizing how “Waste of Thinking” can contribute to societal progress without undermining established norms.

Moreover, in collectivist cultures where group collaboration is prioritized over individualism, the theory can be adapted to encourage collective engagement with discarded ideas. For example, collaborative workshops could be designed to allow groups to collectively reflect on and integrate previously dismissed ideas, fostering a sense of shared ownership and innovation. Additionally, incorporating culturally relevant examples or narratives into the learning process can make the theory more accessible and applicable in such contexts.

Furthermore, variations in educational systems across cultures must be addressed. In some regions, education systems emphasize rote memorization and repetition rather than critical thinking and creativity, which may pose challenges to the adoption of CTT. To address this, curricula can be gradually modified to include activities that build confidence in revisiting and re-evaluating discarded ideas. Over time, these adjustments can help establish CTT as a globally adaptable tool, capable of enhancing creativity and innovation across a wide range of cultural and social contexts.

![New Powerbeats Pro 2 Wireless Earbuds On Sale for $199.95 [Lowest Price Ever]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97217/97217/97217-640.jpg)

![Under-Display Face ID Coming to iPhone 18 Pro and Pro Max [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97215/97215/97215-640.jpg)

![Alleged iPhone 17-19 Roadmap Leaked: Foldables and Spring Launches Ahead [Kuo]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97214/97214/97214-640.jpg)

_Inge_Johnsson-Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![Re-designing a Git/development workflow with best practices [closed]](https://i.postimg.cc/tRvBYcrt/branching-example.jpg)