Talking to Kids About AI

“This is your brain on an LLM”, and other things you shouldn’t say The post Talking to Kids About AI appeared first on Towards Data Science.

I’ve had the

Preparing to Explain Something

I have a few rules of thumb I follow when preparing any talk, for any audience. I need to be very clear in my own mind about what information I intend to impart, and what new things the audience should know after they leave, because this shapes everything about what information I’m going to share. I also want to present my material at an appropriate level of complexity for the audience’s preexisting knowledge — not talking down, but also not way over their heads.

In my day to day life, I’m not necessarily up to speed on what kids already know (or think they know) about AI. I want to make my explanations appropriate to the level of the audience, but in this case I have somewhat limited insight about where they’re coming from already. I have been surprised in some cases that the kids were actually quite aware of things like competition in AI between companies and across international boundaries. A useful exercise when deciding how to frame the content is coming up with metaphors that use concepts or technologies the audience is already very familiar with. Thinking about this also gives you an access point to where the audience is coming from. Beyond that, be prepared to pivot and adjust your presentation approach, if you determine that you’re not hitting the right level. I like to ask kids a little bit about what they think of AI and what they know at the start, so I can start to get that clarity before I’m too far along.

Understanding the Technology

With kids in particular, I’ve got a number of themes I want to cover in my presentations. Regular readers will know I’m a big advocate for laypersons being taught what LLMs and other AI models are trained to do, and what their training data is, because that is vital for us to set realistic expectations for what the models’ results will be. I think it’s easy for anyone, kids included, to be taken in by the anthropomorphic nature of LLM tone, voice, and even “personality” and to lose track of the limitations in reality of what these tools can do.

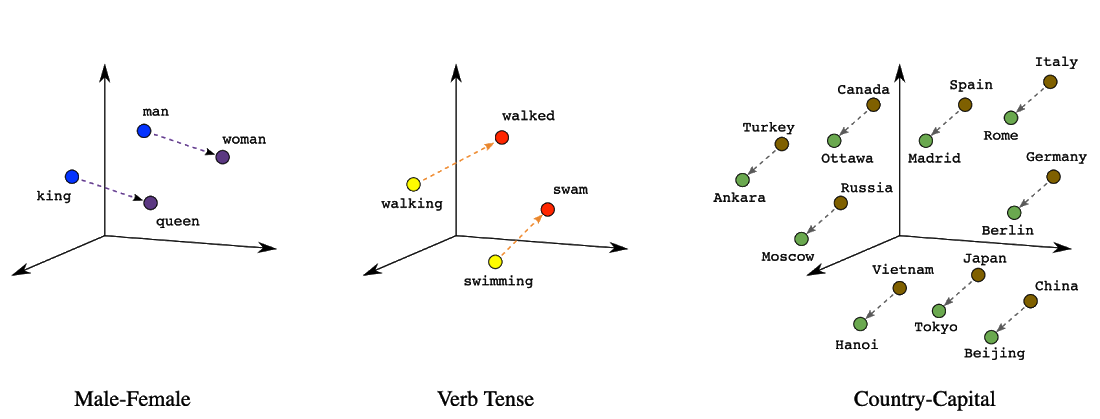

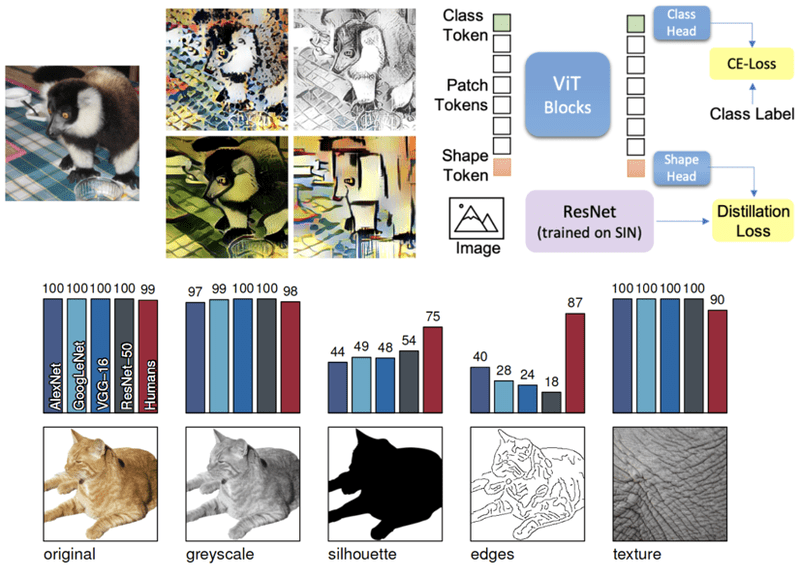

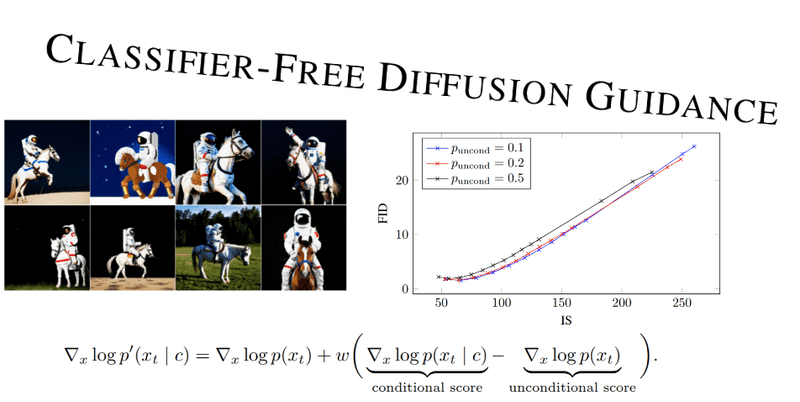

It’s a challenge to make it simple enough to be age-appropriate, but once you tell them about how training works, and how an LLM learns from seeing examples of written material, or a diffusion model learns from text-image pairs, they can interpolate their own intuition about what the results of that might be. As AI agents become more complex, and the underlying mechanisms get tougher to separate out, it’s important for users to know about the building blocks that lead to this capability.

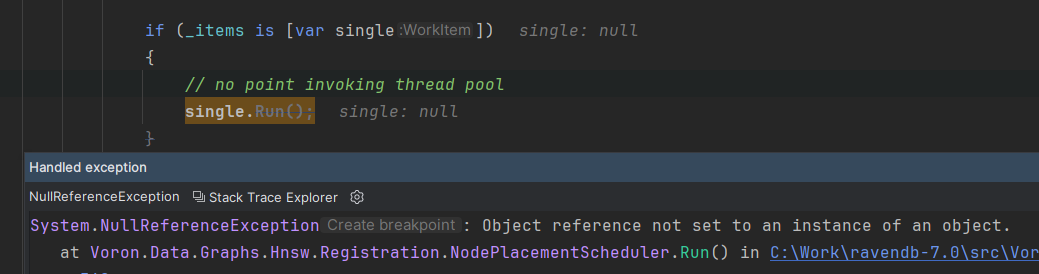

For myself, I start with explaining training as a general concept, avoiding as much technical jargon as possible. When talking to kids, a little anthropomorphizing language can help make things seem a little less mysterious. For example, “we give computers lots of information and ask them to learn the patterns inside.” Next, I’ll describe examples of patterns like those in language or image pixels, because “patterns” by itself is too general and vague. Then, “those patterns it learns are written down using math, and then that math is what is inside a ‘model’. Now, when we give new information to the model, it sends us a response that is based on the patterns it learned.” From there, I give another end to end example, and walk through the process of a simplified training (usually a time series model because it’s pretty easy to visualize). After this, I’ll go into more detail about different types of model, and explain what’s different about neural networks and language models, to the degree that’s appropriate for the audience.

AI Ethics and Externalities

I also want to cover ethical issues related to AI. I think kids who are in later elementary or middle grades and up are perfectly capable of understanding the environmental and social impacts that AI can have. Many kids today seem to me to be quite advanced in their understanding of global climate change and the environmental crisis, so talking about how much power, water, and rare mineral usage is required to run LLMs isn’t unreasonable. It’s just important to make your explanations relatable and age appropriate. As I mentioned earlier, use examples that are relatable and connect to the lived experiences of your audience.

Here’s an example of going from kid experience to the environmental impact of AI.

“So you all have chromebooks to use for homework, right? Do you ever find that when you sit with your laptop on your lap and do work for a long time that the back gets warm? Maybe if you have a lot of files open at once, or watch a lot of videos? So that heating up is the same thing that happens in big computers called servers that run when an LLM is trained or is used, like when you go on chatGPT’s website.

The data centers that keep chatGPT going are full of servers that are all running simultaneously, and all getting pretty darn hot, which isn’t good for the machinery. So, sometimes these data centers use cool water plus some chemicals together piped through tubes that go right over all the servers, and these help cool off the machines and keep them running. However, this means that a ton of water is being used, mixed with chemicals, and heated up as it goes through these systems, and it can mean that that water isn’t available for people to use for other things like farms or drinking water.

Other times, these data centers use big air conditioners, which take a lot of electricity to run, which means there may not be enough electricity for our houses or for businesses. Electricity is also sometimes made by burning coal in power plants, which puts out exhaust into the air and increases pollution too. ”

This brings the kid’s experience into the conversation, and gives them a tangible way to relate to the concept. You can do similar kinds of discussion around copyright ethics and stealing content, using artists and creators familiar to the Children, without having to get deep in the weeds of IP law. Deepfakes, both sexual and otherwise, are certainly a topic lots of kids know about too, and it’s important that children are aware of the risks those present to individuals and the community as they use AI.

It can be scary, especially for younger kids, when they start to grasp some of the unethical applications of AI or global challenges it creates, and realize how powerful some of this stuff can be. I’ve had kids ask “how can we fix it if someone teaches AI to do bad things?”, for example. I wish I had better answers for that, because I had to essentially say “AI already sometimes has the information to do bad things, but there are also lots of people working hard to make AI more safe and prevent it from sharing any bad information or instructions on how to do bad things.”

Unpacking the Idea of “Truth”

The anthropomorphizing of AI problem is true for adults and kids both – we tend to trust a friendly, confident voice when it tells us things. A large part of the problem is that the LLM voice telling us things is frequently friendly, confident, and wrong. The concept of media literacy has been an important topic in pedagogy for years now, and expanding this to LLMs is a natural progression. Just like students (and adults) need to learn to be critical consumers of information generated by other people or corporations, we need to be critical and thoughtful consumers of computer-generated content.

I think this goes along with understanding the tech, too. When I explain that an LLM’s job is to learn and replicate human language, at the simplest level by selecting the probable next word in a series based on what came before, it makes sense when I go on to say that the LLM can’t understand the idea of “truth”. Truth isn’t part of the training process, and at the same time truth is a really hard concept even for people to figure out. The LLM might get the facts right frequently, but the blind spots and potential mistakes are going to show up from time to time, by the nature of probability. As a result, kids who use it need to be very conscious of the fallibility of the tool.

This lesson actually has value beyond just the use of AI, however, because what we’re teaching is about dealing with uncertainty, ambiguity, and mistakes. As Bearman and Ajjawi (2023) note, “pedagogy for an AI-mediated world involves learning to work with opaque, partial and ambiguous situations, which reflect the entangled relationships between people and technologies.” I really like this framing, because it comes back around to something I think about a lot — that LLMs are created by humans and reflect back interpretations of human-generated content. When kids learn how models come to exist, that models are fallible, and that their output originates from human-generated input, they’re getting familiar with the blurry nature of how technology works today in our society more broadly. (In fact, I highly recommend the article in full for anyone who’s thinking about how to teach kids about AI themselves.)

A side note on images and video

As I’ve written about before, the profusion of deepfake/”AI slop” video and image content online creates a lot of difficult questions. This is another area where I think giving kids information is important, because it’s easy to absorb misinformation or outright lies through convincing visual content. This content is also one step away from the actual creation process for most kids, as a lot of this material is being shared widely on social media, and is unlikely to be labeled. Talking to kids about what tell-tale signs help to detect AI generated material can help, as well as general critical media literacy skills like “if it’s too good to be true, it’s probably fake” and “double check things you hear in this kind of post”.

Cheating

However much we explain the ethical issues and the risks that the LLM will be wrong, these AI tools are incredibly useful and seductive, so it’s understandable that some kids will resort to using them to cheat on homework and in school. I’d like to say that we need to just reason with them, and explain that learning the skills to do the homework is the point, and if they don’t learn it they’ll be missing capabilities they need for future grades and later life… but we all know that kids are very rarely that logical. Their brains are still developing, and this sort of thing is hard even for adults to reason about at times.

There are two approaches you might take, essentially: find ways to make schoolwork harder or impossible to cheat on, or incorporate AI into the classroom under the assumption that kids are going to have it at their disposal in the future. Now, monitored work in a classroom setting can give kids a chance to learn some skills they need to have without digital mediation. However, as I mentioned earlier, media literacy really has to include LLMs now, and I think supervised use of LLMs by an informed instructor can have plenty of pedagogical value. In addition, it’s really impossible to “AI-proof” homework that’s done outside of direct instructor supervision, and we should recognize that. I don’t want to make it sound like this is easy, however — see below in the Further Reading section for a number of scholarly articles on the broad challenges of teaching AI literacy in the classroom. Teachers have a very challenging task to try not only to keep up on the technology themselves and evolve their pedagogy to fit the times, but also to try and give their students the information they need to use AI responsibly.

Learning from the Example of Sex Ed

In the end, the question is what exactly we ought to be recommending kids do and not do in a world that contains AI, in the classroom and beyond. I’m rarely an advocate for banning or prohibition of ideas, and I think the example of science-based, age-appropriate comprehensive sex Education presents a good lesson. If children are not given accurate information about their bodies and sexuality, they don’t have the knowledge necessary to make informed, responsible decisions in that area. We learned this when abstinence-only sex ed made teen pregnancy rates go through the roof in the early 2000’s. Adults will not be present to enforce mandates when kids are making the difficult decisions about what to do in challenging circumstances, so we need to make sure the kids are equipped with the information required to make those decisions responsibly themselves, and this includes ethical guidance but also factual information.

Modeling Responsibility

One last thing that I think is important to mention is that adults should be modeling responsible behavior with AI too. If teachers, parents, and other adults in kids’ lives are not critically literate about AI, then they aren’t going to be able to teach kids to be critical and thoughtful consumers of this technology either.

A recent New York Times story about how teachers use AI made me a little frustrated. The article doesn’t reflect a great understanding of AI, conflating it with some basic statistics (a teacher analyzing student data to help personalize his teaching to their levels is both not AI and not new or problematic), but it does start a conversation about how adults in kids’ lives are using AI tools, and it mentions the need for those adults to model transparent and critical uses of it. (It also briefly grazes the issue of for-profit industry pushing AI into the classroom, which seems like a problem deserving more time — maybe I’ll write about that down the road.)

To counter one assertion of the piece, I wouldn’t complain about teachers using LLMs to do a first pass at grading written material, as long as they are monitoring and validating the output. If the grading criteria are around grammar, spelling, and writing mechanics, an Llm is probably suitable based on how it’s trained. I wouldn’t want to blindly trust an LLM on this without a human taking at least a quick look, but human language is in fact what it’s designed to understand. The idea that “the student had to write it, so the teacher should have to grade it” is silly, because the purpose of the exercise is for the student to learn. Teachers already know the writing mechanics, this is not a project that is meant to force teachers to learn something that is only achievable by manually grading. I think the NYT knows this, and that the framing was mostly for clickbait purposes, but it’s worth saying clearly.

This point goes back, once again, to my earlier section about understanding the technology. If you confidently understand what the training process looks like, then you can decide whether that process would produce a tool that’s capable of managing a task, or not. But automating grading has been part of schooling for decades at least — anyone who’s filled out a scantron sheet knows that.

This technology’s development is forcing some amount of adaptation in our education system, but we can’t put that genie back in the bottle now. There are definitely some ways that AI can have positive effects on education (often cited examples are personalization and saving teachers time that can then be put towards direct student services), but as with most things I’m an advocate for a realistic view. As I believe most educators are only too well aware, education can’t just go on as it did before LLMs entered our lives.

Conclusion

Kids are smarter than we sometimes give them credit for, and I think they are capable of understanding a lot about what AI means in our world. My advice is to be transparent and forthright about the realities of the technology, including advantages and disadvantages it represents to us as individuals and to our broader society. How we use it ourselves will model to kids either positive or negative choices that they’re going to notice, so being thoughtful about our actions as well as what we say is key.

For more of my work, visit www.stephaniekirmer.com.

If you’d like to learn more about Skype a Scientist, visit https://www.skypeascientist.com/

Further Reading

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/14/us/schools-ai-teachers-writing.html

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3194801

https://www.stephaniekirmer.com/writing/environmentalimplicationsoftheaiboom

https://www.stephaniekirmer.com/writing/seeingourreflectioninllms

https://www.stephaniekirmer.com/writing/machinelearningspublicperceptionproblem

https://www.stephaniekirmer.com/writing/whatdoesitmeanwhenmachinelearningmakesamistake

https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjet.13337

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666920X21000357

https://www.stephaniekirmer.com/writing/theculturalimpactofaigeneratedcontentpart1

Additional Articles about Pedagogical Approaches to AI

For anyone who’s teaching these topics or would like a deeper dive, here are a few articles I found interesting as I was researching this.

https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjet.13337

https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3408877.3432530 — an early college level curriculum study

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666920X22000169 — a preschool/early elementary level curriculum study

https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3311890.3311904 — analysis of SES and national variation in AI learning among young children

The post Talking to Kids About AI appeared first on Towards Data Science.

![Apple Developing AI 'Vibe-Coding' Assistant for Xcode With Anthropic [Report]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97200/97200/97200-640.jpg)

![Apple's New Ads Spotlight Apple Watch for Kids [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/97197/97197/97197-640.jpg)

_Andy_Dean_Photography_Alamy.jpg?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale#)

![[The AI Show Episode 145]: OpenAI Releases o3 and o4-mini, AI Is Causing “Quiet Layoffs,” Executive Order on Youth AI Education & GPT-4o’s Controversial Update](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20145%20cover.png)

![From Art School Drop-out to Microsoft Engineer with Shashi Lo [Podcast #170]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1746203291209/439bf16b-c820-4fe8-b69e-94d80533b2df.png?#)