4 big ways tech could go backward in 2025

By now, you’ve heard of the U.S.’s decision to levy tariffs on imports—all goods made in China, as well as select materials worldwide, like steel and aluminum. At the time of this article’s publishing, taxes on products coming from Canada and Mexico also were likely to begin early April, with additional tariffs proposed for more materials and products worldwide. I covered the details about these tariffs in a FAQ, as well as a set of highlights for a shorter way to get up to speed on the situation. I also created a breakout of sample cost increases so you could better see what actual purchases could look like. But most news has focused on the immediate dollars-and-cents effect of these new taxes. What’s been talked about less are the other ways tariffs will impact the tech industry—consequences that could dampen or even drive back certain aspects that we currently take for granted. At best, we’ll see a temporary blow. At worst, we could feel this hit for years to come. Harder to obtain Technology has become more available to the masses over time. Long ago, personal computers were a rare luxury, found only in homes of enthusiasts or the well-to-do. But as popularity rose, devices and hardware became easier to get. People wanted to spend their money on fresh gear—and so supply became more plentiful. Remember when EVGA made graphics cards? Yeah, they don’t any longer, after looking at the cost of that part of their business. Let’s hope the tariffs don’t cause other companies to make similar moves within tech.Brad Chacos / Foundry But when prices go up, demand goes down. Companies already have an incentive to slow the rollout of new products due to the economic instability brought about by the tariffs. If you add on a weakened appetite from consumers for discretionary purchases, vendors have reason to pull back on the production. They may become slower to release successors to products or even a wider variety of products. In particular, smaller companies decide to pause or stop product lines. Industry insiders expressed this very sentiment to me when discussing the tariffs and their effect. Without the ability to make accurate forecasts, businesses have to proceed with more caution. They’ll either produce less of their usual devices or hardware—or opt out of selling certain items altogether. After years of ever-growing options for consumers, shrinking down to fewer choices will be a sad step backward. Price stagnation (or even increases) Intel’s Kaby Lake Core i7-7700X launched just a couple of months before AMD’s first-generation Ryzen CPUs, sporting a 4-core, 8-thread processor. By fall, its Coffee Lake Core i7-8700K successor had added two more cores and four more threads. Competition makes a difference.Adam Patrick Murray / Foundry Innovation and competition help lower costs for technology. Manufacturing becomes more efficient, growing demand spreads production costs over a wider field, and/or the tech is succeeded by something even fresher. But if tech gear becomes less varied and harder to get, those factors won’t be as dependable as an influence on price. How much you’ll pay for a laptop, phone, or piece of hardware will likely stick where it is—or go up. As my colleague Gordon Mah Ung loved to point out, Intel sold consumers 4-core, 8-thread CPUs for years, always at similar MSRPs. And when Team Blue launched its first 10-core processor, the suggested price was a staggering $1,723. Fast forward a year, after AMD released its first generation of Ryzen chips, and Intel’s top consumer chip had inched up in core count, with the $359 Intel Core i7-8700K sporting 6 cores and 12 threads. Its closest rivals? The $329 Ryzen 7 1700 and $399 Ryzen 7 1700X, both of which sported 8 cores and 16 threads. This history lesson shows that consumers get less value when fewer options exist. Companies can charge whatever they want when faced with less pressure to keep pushing the envelope. Slower release of new products Should early adopters become more reluctant to try out new gadgets, companies could stop trying novel new form factors, like this tri-fold smartphone.Luke Baker If you’re a company facing economic uncertainty, how much would you want to invest in different products? Likewise, if you’re a consumer looking at devices with fewer or smaller upgrades that cost as much as the previous model, will you want to buy anything new? It’s a bit of a standoff, and one that the tariffs could spark. For example, let’s say you’re used to buying a replacement phone every two years. But if the features don’t change dramatically, and prices remain high (especially for flagship models), perhaps you’ll stick to what you’ve already got in your pocket. Companies might then not push novel form factors as hard, like tri-fold phones and other variants. Similarly, Nvidia and AMD could continue to delay their attention to budget ga

By now, you’ve heard of the U.S.’s decision to levy tariffs on imports—all goods made in China, as well as select materials worldwide, like steel and aluminum. At the time of this article’s publishing, taxes on products coming from Canada and Mexico also were likely to begin early April, with additional tariffs proposed for more materials and products worldwide.

I covered the details about these tariffs in a FAQ, as well as a set of highlights for a shorter way to get up to speed on the situation. I also created a breakout of sample cost increases so you could better see what actual purchases could look like.

But most news has focused on the immediate dollars-and-cents effect of these new taxes. What’s been talked about less are the other ways tariffs will impact the tech industry—consequences that could dampen or even drive back certain aspects that we currently take for granted. At best, we’ll see a temporary blow. At worst, we could feel this hit for years to come.

Harder to obtain

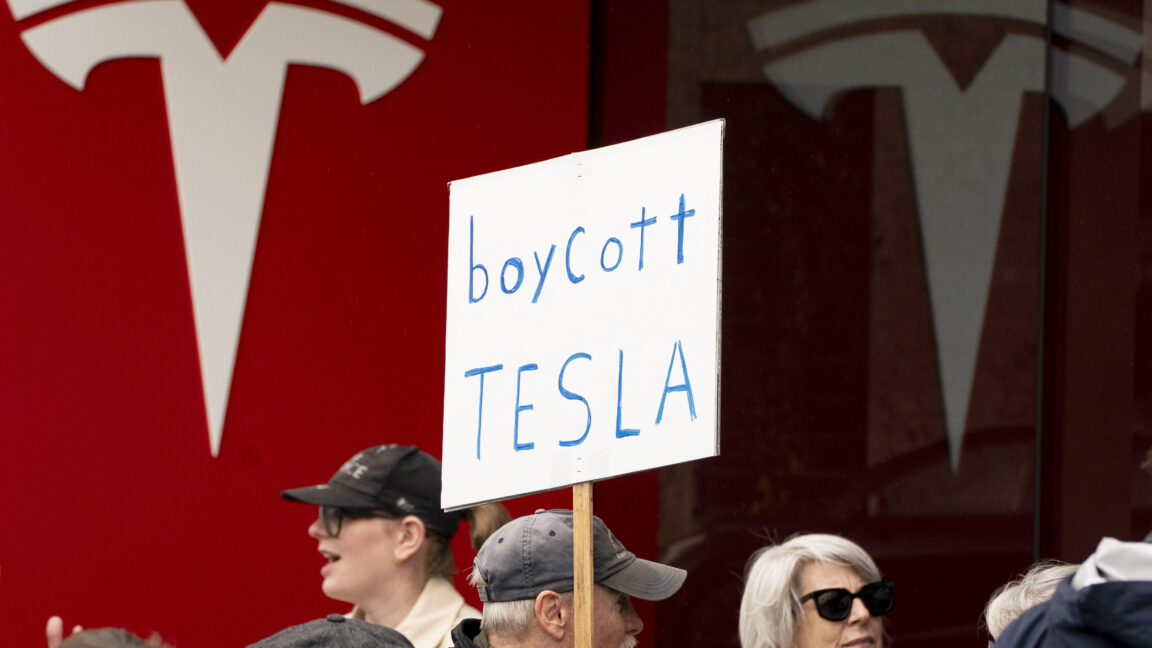

Technology has become more available to the masses over time. Long ago, personal computers were a rare luxury, found only in homes of enthusiasts or the well-to-do. But as popularity rose, devices and hardware became easier to get. People wanted to spend their money on fresh gear—and so supply became more plentiful.

Brad Chacos / Foundry

But when prices go up, demand goes down. Companies already have an incentive to slow the rollout of new products due to the economic instability brought about by the tariffs. If you add on a weakened appetite from consumers for discretionary purchases, vendors have reason to pull back on the production. They may become slower to release successors to products or even a wider variety of products. In particular, smaller companies decide to pause or stop product lines.

Industry insiders expressed this very sentiment to me when discussing the tariffs and their effect. Without the ability to make accurate forecasts, businesses have to proceed with more caution. They’ll either produce less of their usual devices or hardware—or opt out of selling certain items altogether.

After years of ever-growing options for consumers, shrinking down to fewer choices will be a sad step backward.

Price stagnation (or even increases)

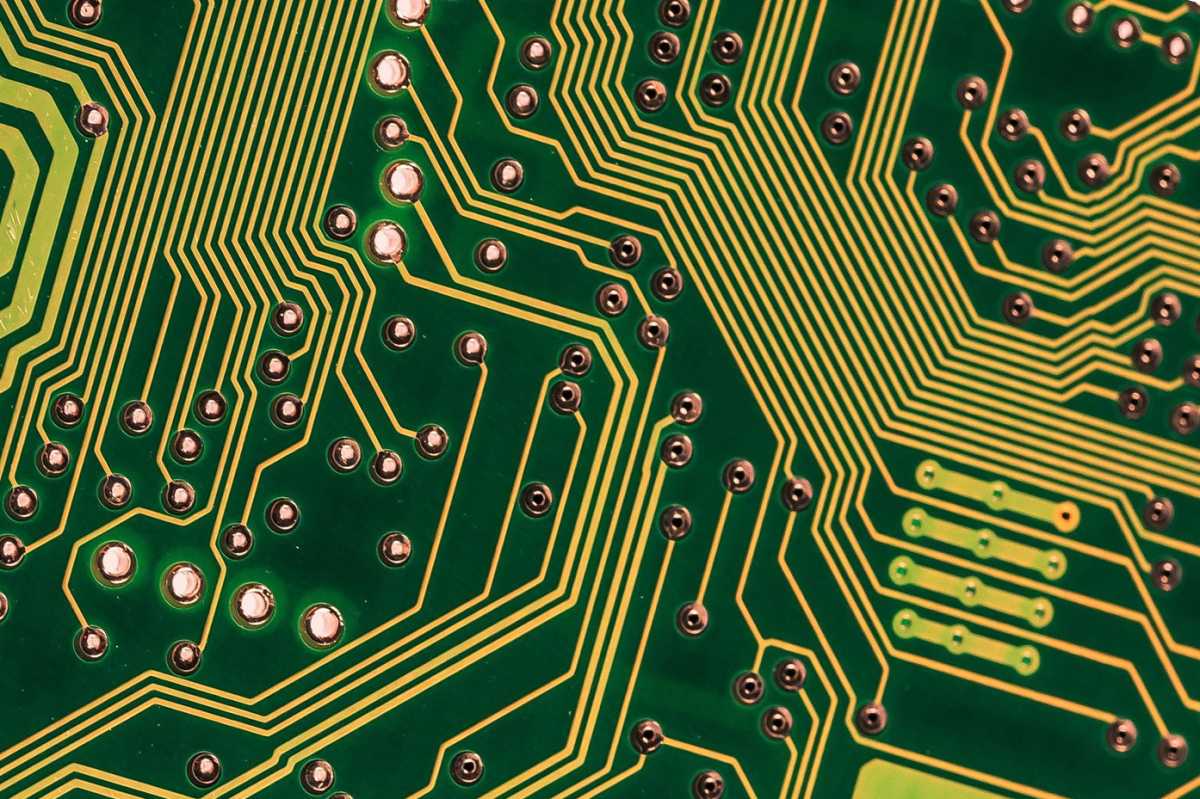

Adam Patrick Murray / Foundry

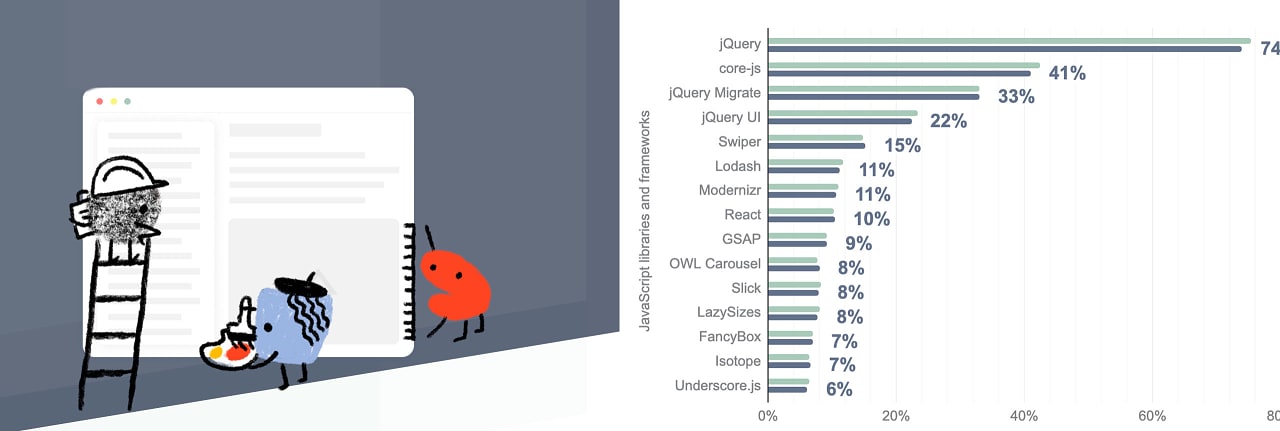

Innovation and competition help lower costs for technology. Manufacturing becomes more efficient, growing demand spreads production costs over a wider field, and/or the tech is succeeded by something even fresher.

But if tech gear becomes less varied and harder to get, those factors won’t be as dependable as an influence on price. How much you’ll pay for a laptop, phone, or piece of hardware will likely stick where it is—or go up. As my colleague Gordon Mah Ung loved to point out, Intel sold consumers 4-core, 8-thread CPUs for years, always at similar MSRPs. And when Team Blue launched its first 10-core processor, the suggested price was a staggering $1,723.

Fast forward a year, after AMD released its first generation of Ryzen chips, and Intel’s top consumer chip had inched up in core count, with the $359 Intel Core i7-8700K sporting 6 cores and 12 threads. Its closest rivals? The $329 Ryzen 7 1700 and $399 Ryzen 7 1700X, both of which sported 8 cores and 16 threads.

This history lesson shows that consumers get less value when fewer options exist. Companies can charge whatever they want when faced with less pressure to keep pushing the envelope.

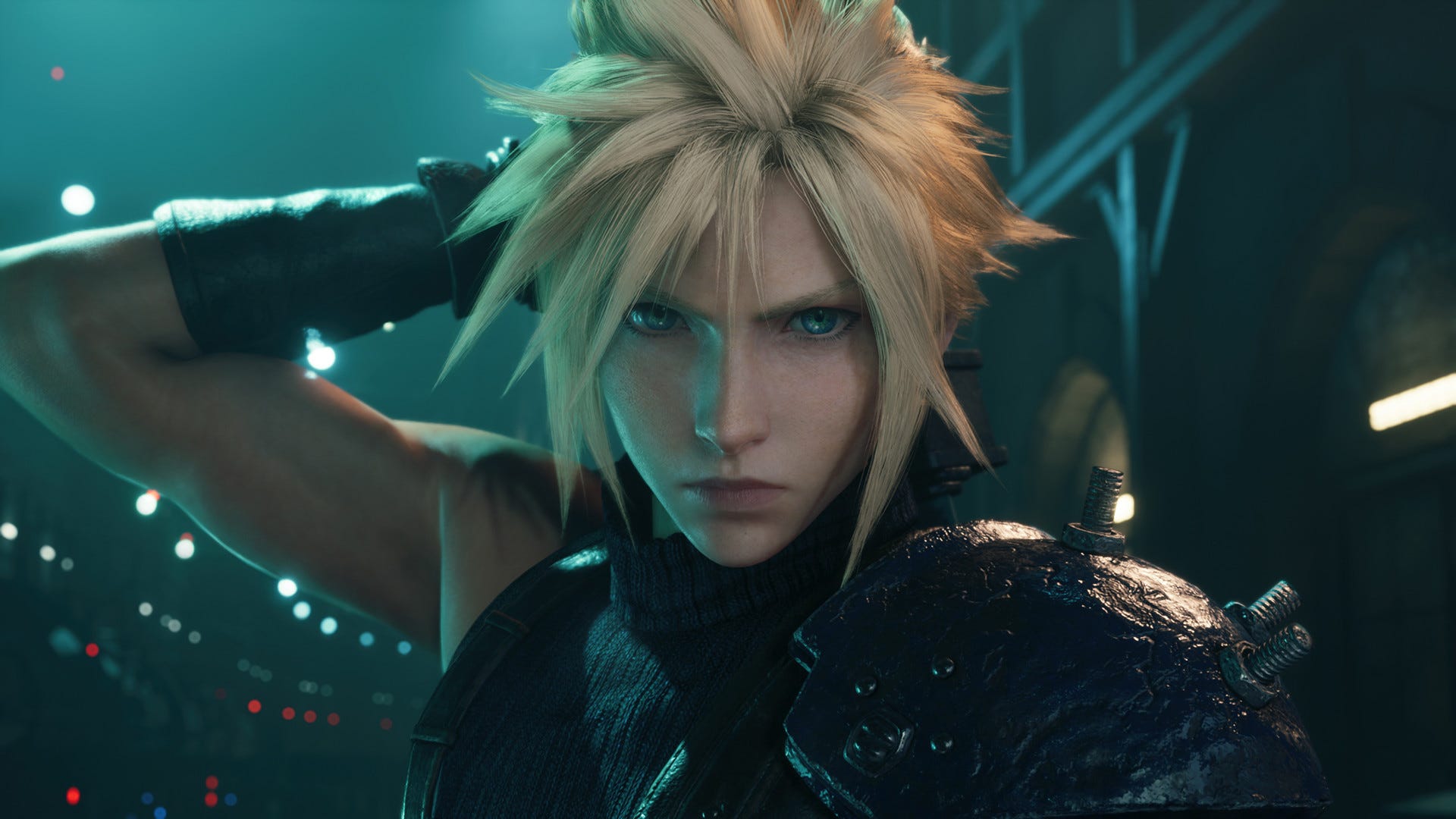

Slower release of new products

Luke Baker

If you’re a company facing economic uncertainty, how much would you want to invest in different products? Likewise, if you’re a consumer looking at devices with fewer or smaller upgrades that cost as much as the previous model, will you want to buy anything new?

It’s a bit of a standoff, and one that the tariffs could spark. For example, let’s say you’re used to buying a replacement phone every two years. But if the features don’t change dramatically, and prices remain high (especially for flagship models), perhaps you’ll stick to what you’ve already got in your pocket. Companies might then not push novel form factors as hard, like tri-fold phones and other variants.

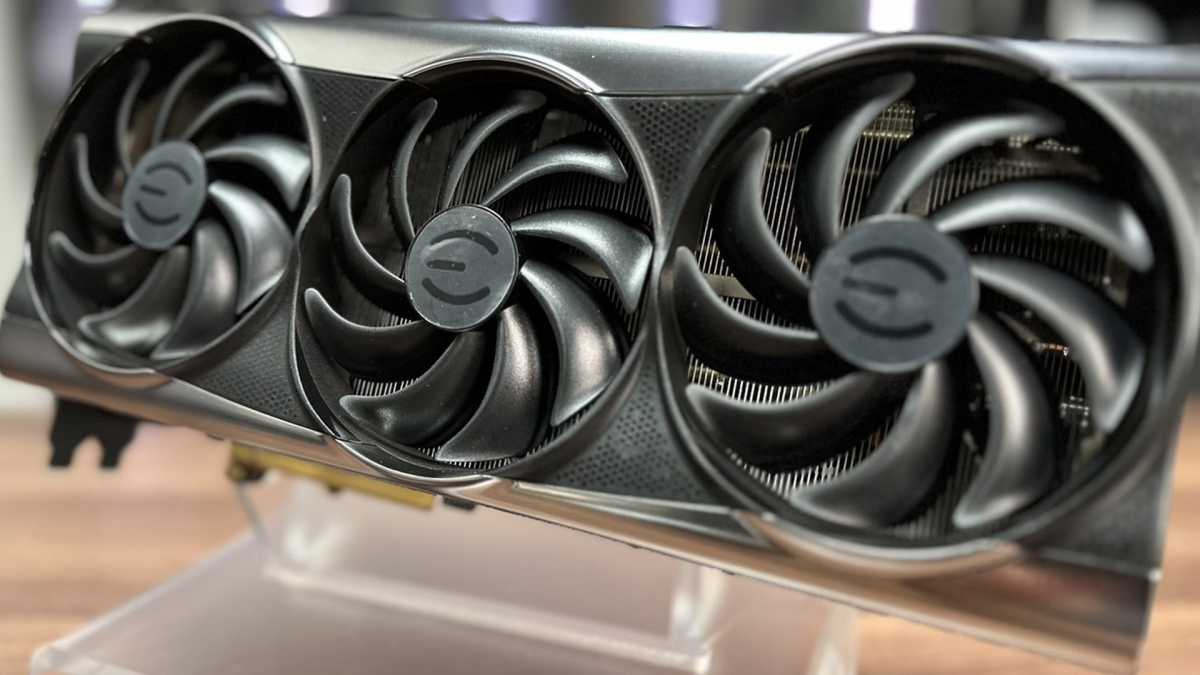

Similarly, Nvidia and AMD could continue to delay their attention to budget gamers, instead choosing to focus on graphics cards that will bring in more cash. Sure, Intel is the lone holdout for the budget range, but its market share remains low, and its launches aren’t as regular. Budget gamers might then continue to hold out, biding their time with progressively lower graphics settings and frame rates. (But real talk, if your GTX 970 still does it for you, keep rocking that GPU until its well-deserved retirement.)

So while engineers will continue to announce newer protocols and standards (think Wi-Fi 7 or PCIe 7.0), the time to an actual launch may be much further in the future than we’re used to. And that pace change could feel like a screeching halt compared to the boom of the past couple of decades, depending on how big a slowdown is.

Unpredictable pricing

Michael Schwarzenberger / Pixabay

Until recent years, technology’s progress also often resulted in a predictable routine for prices, too. Current devices got cheaper, and the stuff that replaced them often stayed the same price or even lowered, thanks to improved manufacturing or higher demand.

Before the tariffs, that reliability in pricing trends started to waver due to factors like rising production costs. And now with these additional taxes dropped on top, we consumers may no longer be able to trust in steady pricing.

First, as companies shift manufacturing locations, their logistical costs will increase. But how much is still to be determined, based on resources (e.g., new staff hiring, training, etc.) and the ability for a business to absorb current tariff costs. Some larger corporations may take a hit in an effort to keep their part of the industry more stable, for example.

Additional tariffs could also cause sudden changes to MSRPs. Given how the current U.S. import tariffs were enacted, more could be announced very suddenly as well, with a notice of just a few days.

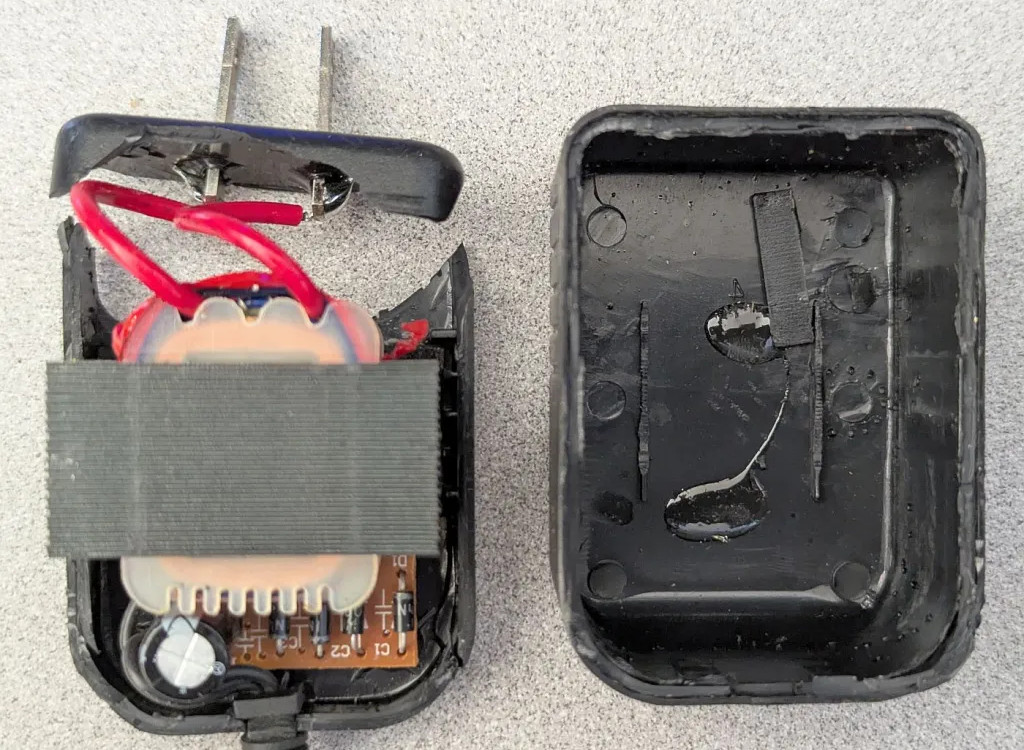

EVGA

The prospect of new tariffs looms large, too—in February, the U.S. executive branch proposed a 25 percent tariff on all semiconductors, with the intent to sharply raise the tax over time. More recently, a 25 percent tariff on copper was suggested. (You’ll find copper in circuit boards, wiring, and a lot more related to tech.) If these tariffs stack on top of the existing 20 percent on all Chinese-made goods, you could see a sharp rise in costs for products with multiple components affected by these additional taxes.

Another wrinkle: When I last spoke with industry insiders, multiple sources told me they were still learning exactly how the tariffs would be applied. So they themselves are scrambling to adjust and adapt.

Finally, if costs go up and availability decreases (as discussed above), you may have more trouble predicting actual retail prices. Street prices could go a bit wild, too. We can look at the GPU market for a glimpse into that chaotic, terrible universe: Few cards are available at the announced price, and any remaining stock is higher due to partner cards adding on extras. Any other cards are only available through resellers at huge markups.

Before the pandemic, you could easily shop for devices and hardware, with the expectation of regular sales or discounts. Now surplus budgeting may be a requirement whenever you’re preparing for a new purchase.

![Apple Shares Official Trailer for 'Fountain of Youth' Starring John Krasinski, Natalie Portman [Video]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96902/96902/96902-1280.jpg)

![Apple is Still Working on Solid State iPhone Buttons [Rumor]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96904/96904/96904-640.jpg)

![Nomad Goods Launches 15% Sitewide Sale for 48 Hours Only [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96899/96899/96899-640.jpg)

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![Is this a suitable approach to architect a flutter app? [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/4hMHGb1L.png)

![From broke musician to working dev. How college drop-out Ryan Furrer taught himself to code [Podcast #166]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743189826063/2080cde4-6fc0-46fb-b98d-b3d59841e8c4.png?#)