Zink is Zero Ink — Sort Of

When you think of printing on paper, you probably think of an ink jet or a laser printer. If you happen to think of a thermal printer, we bet you …read more

When you think of printing on paper, you probably think of an ink jet or a laser printer. If you happen to think of a thermal printer, we bet you think of something like a receipt printer: fast and monochrome. But in the last few decades, there’s been a family of niche printers designed to print snapshots in color using thermal technology. Some of them are built into cameras and some are about the size of a chunky cell phone battery, but they all rely on a Polaroid-developed technology for doing high-definition color printing known as Zink — a portmanteau of zero ink.

For whatever reason, these printers aren’t a household name even though they’ve been around for a while. Yet, someone must be using them. You can buy printers and paper quite readily and relatively inexpensively. Recently, I saw an HP-branded Zink printer in action, and I wasn’t expecting much. But I was stunned at the picture quality. Sure, it can’t print a very large photo, but for little wallet-size snaps, it did a great job.

The Tech

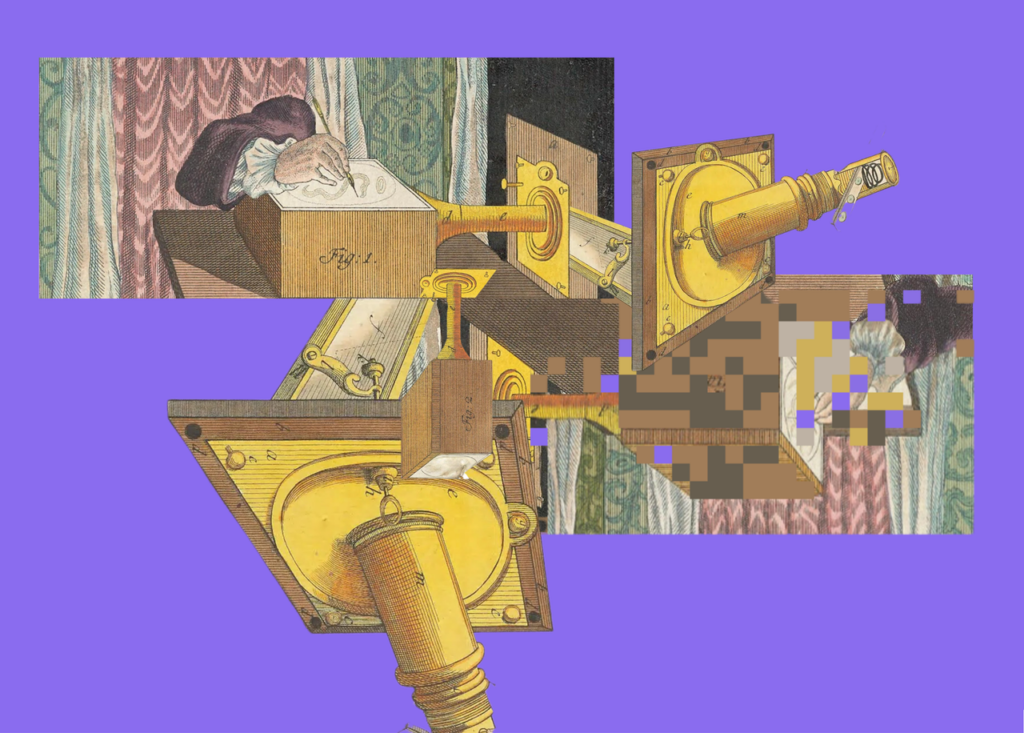

Polaroid was well known for making photographic paper with color layers used in instant photography. In the 1990s, the company was looking for something new. The Zink paper was the result. The paper has three layers of amorphochromic dyes. Initially, the dye is colorless, but will take on a particular color based on temperature.

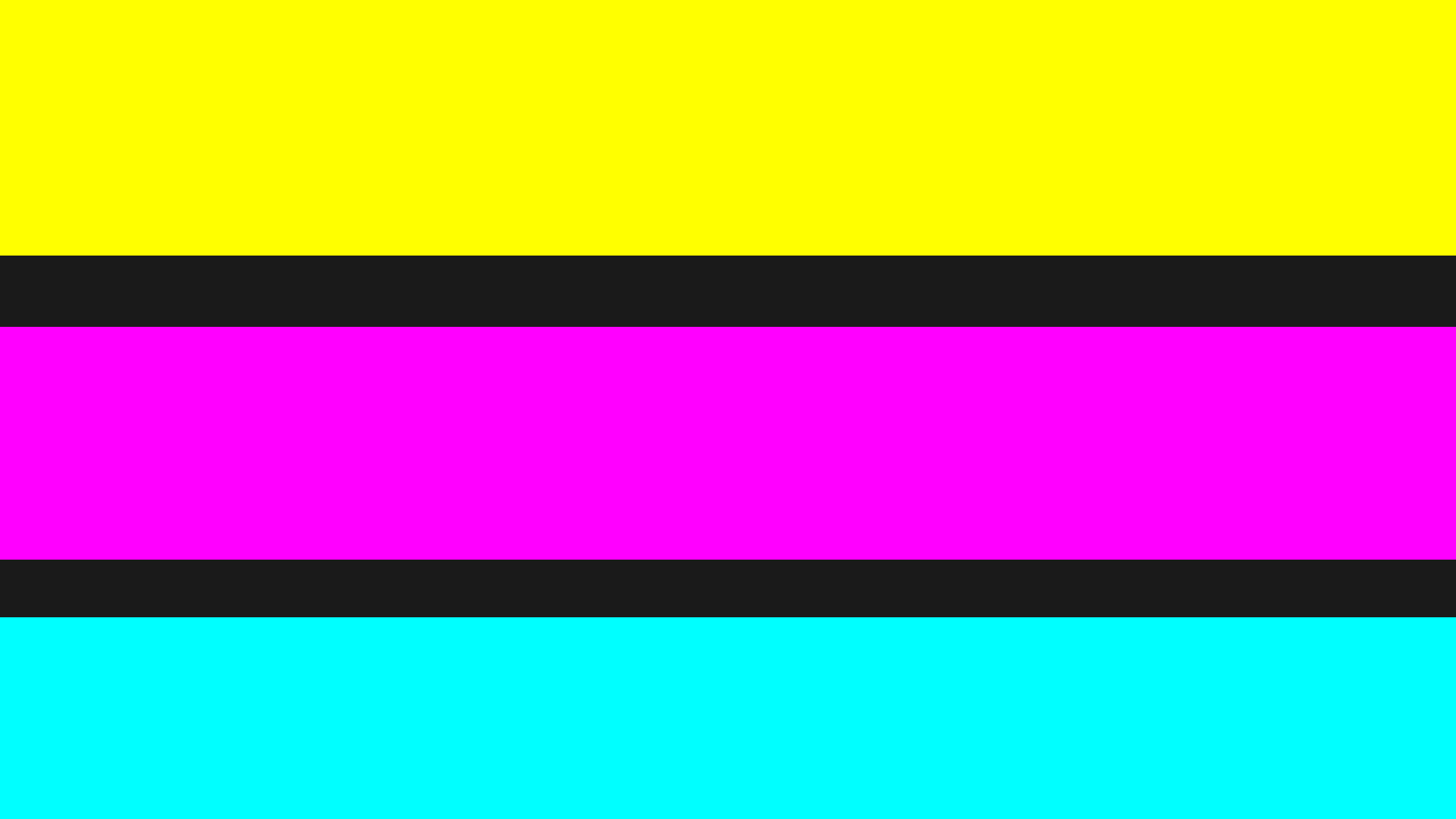

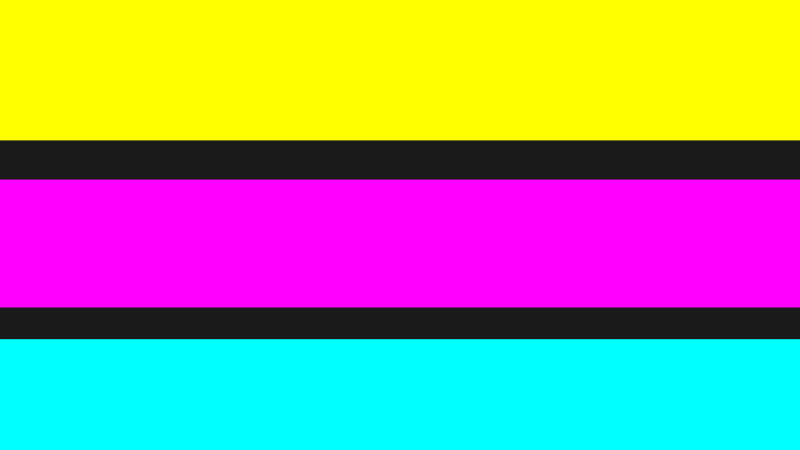

The key to understanding the process is that you can control the temperature that will trigger a color change. The top layer of the paper requires high heat to change. The printer uses a very short pulse, so that the top layer will turn yellow, but the heat won’t travel down past that top layer.

The middle layer — magenta — will change at a medium heat level. But to get that heat to the layer, the pulse has to be longer. The top layer, however, doesn’t care because it never gets to the temperature that will cause it to turn yellow.

The bottom layer is cyan. This dye is set to take the lowest temperature of all, but since the bottom heats up slowly, it takes an even longer pulse at the lower temperature. The top two layers, again, don’t matter since they won’t get hot enough to change. A researcher involved in the project likened the process to fried ice cream. You fry the coating at a high temperature for a short time to avoid melting the ice cream. Or you can wait, and the ice cream will melt without affecting the coating.

The pulses range from about 500 microseconds for yellow up to 10 milliseconds for cyan. The dyes need to not erroneously react to, say, sunlight, so the temperature targets ranged from 100 °C to 200 °C. A solvent melts at the right temperature and causes the dye to change color. So, technically, the dye doesn’t change color with heating. The solvent causes it to change color, and the heat releases the solvent.

It works well, as you can see in the short clip below. There’s no audio, but the printer does make a little grinding noise as it prints:

The History

Zink started as research from Polaroid. The company’s instant film used color dyes that diffuse up to the surface unless blocked by a photosensitive chemical. The problem is that diffusion is difficult to control, so they were interested in finding another alternative.

Chemists at Polaroid had the idea of using a colorless chemical until exposed to light. They would eventually give up in the 1980s, but revisited the idea in the 1990s when digital photography started eroding their market share.

One program designed to save the company was to build a portable printer, and the earlier research on colorless dyes came back around. Thermal print heads were already available. You only needed a paper showing different colors based on some property the print head could control.

The team had success in the early 2000s. A 2″ x 3″ print required 200 million pulses of heat, but the results were impressive, although not quite as good as they needed to be for a commercial device. Unfortunately, in 2001, Polaroid filed for bankruptcy. The company changed hands a few times until the new owner decided it was too expensive to continue researching the new printer technology.

A New Hope

The people driving the project knew they had to find a buyer for the technology if they wanted to continue. Many companies were interested in a finished product, but not as interested in a prototype.

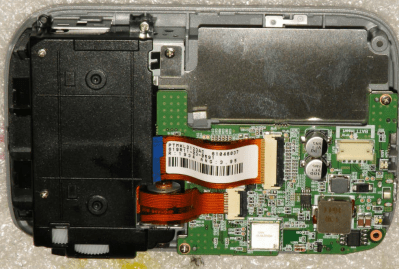

They were using a modified but existing thermal printer from Alps to demonstrate the technology, and when they showed it to Alps, they immediately signed on as a partner to make the hardware. This was enough to persuade an investor to step up and pull the company out of what was left of Polaroid.

Calibration

Of course, there were trials, but the new company, Zink Imaging, managed to roll out a commercially viable product. One problem solved was dealing with the slightly different paper between batches. The answer was to have each pack of paper have a barcode on the first sheet that the printer uses to calibrate itself.

Zink’s business model involves selling the paper it makes. It licenses its technology to companies like Polaroid, Dell, Kodak, and HP, which then have the usual manufacturing partners build the printers. Search your favorite retailer for “zink printer” and you’ll find plenty of options. The 2″ x 3″ paper is still popular, although you can get 4″ x 6″ printers, too.

Of course, saying it is inkless isn’t really true. The “ink” is in the paper and, as you might expect, the paper isn’t that cheap. On the other hand, inkjet ink is also expensive, and you don’t have to worry about a printer clogging up if it is unused for a few months.

More…

While Skymall no longer sells from airplanes, their YouTube channel shows a high-level view of how the printer works in a video, which you can see below.

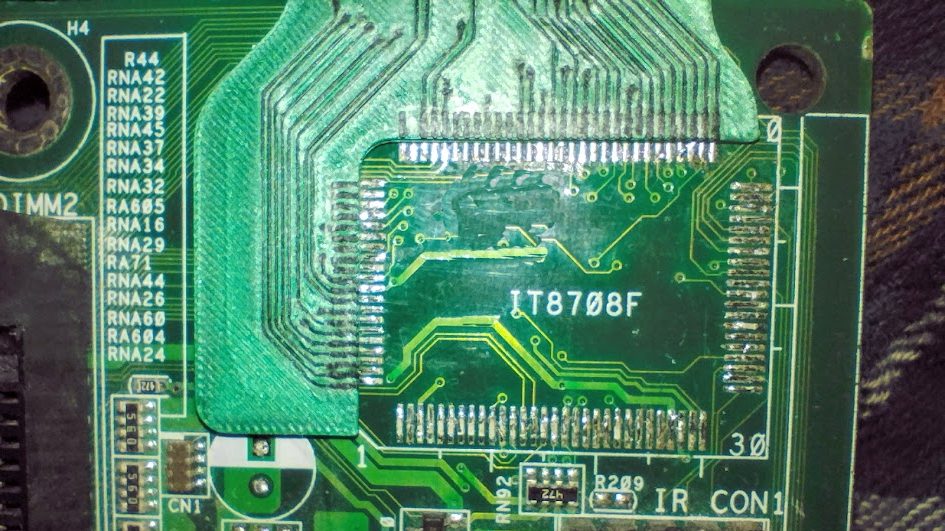

If you were hoping for a teardown, check out the FCC filings to find plenty of internal pictures (we’ve mentioned how to do this before).

We are always surprised these aren’t more common. Do you have one of these printers? Let us know in the comments. The best use we’ve seen of one of these was in a fake Polaroid camera. If you really want nostalgic photography, break out your 3D printer.

![T-Mobile says it didn't compromise its values to get FCC to approve fiber deal [UPDATED]](https://m-cdn.phonearena.com/images/article/169088-two/T-Mobile-says-it-didnt-compromise-its-values-to-get-FCC-to-approve-fiber-deal-UPDATED.jpg?#)

![Nomad Goods Launches 15% Sitewide Sale for 48 Hours Only [Deal]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96899/96899/96899-640.jpg)

![Apple Watch Series 10 Prototype with Mystery Sensor Surfaces [Images]](https://www.iclarified.com/images/news/96892/96892/96892-640.jpg)

![[The AI Show Episode 142]: ChatGPT’s New Image Generator, Studio Ghibli Craze and Backlash, Gemini 2.5, OpenAI Academy, 4o Updates, Vibe Marketing & xAI Acquires X](https://www.marketingaiinstitute.com/hubfs/ep%20142%20cover.png)

![Is this a suitable approach to architect a flutter app? [closed]](https://i.sstatic.net/4hMHGb1L.png)

![From broke musician to working dev. How college drop-out Ryan Furrer taught himself to code [Podcast #166]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1743189826063/2080cde4-6fc0-46fb-b98d-b3d59841e8c4.png?#)